Mastering Clinical Medicine (Part 1)

“What do you think is wrong?”, the consultant asked.

I had no idea.

I looked back at the patient that I had just examined, lying on the bed in front of me, hoping for a clue.

“Err… a problem with his bowels… awaiting surgery?”, I answered.

A flash of disappointment crossed the consultant’s face.

He grabbed my hand, took it over to the patient and used it to prod the patient in the right upper quadrant.

“Do you feel that? That’s his liver. It’s 3-4 cm below the costal margin. He has hepatomegaly (an enlarged liver).”

We left the patient’s bed side and wrapped up the teaching session.

The frustrating thing was I had actually felt that liver during my original examination, I just hadn’t realised that it was large.

I’d performed abdominal examinations stacks of times before. My routine was slick. I knew the appropriate technique for palpating the liver. I’d been taught how you should bend from the metacarpophalangeal joint and to always keep your hand in contact with the abdomen.

I could also reel off causes of hepatomegaly, from alcoholic liver disease to infectious hepatitis, from malignancy to heart failure. (Of course, I’d learnt this well using Spaced Repetition and learning for understanding!)

Despite all of this, in that moment I missed the diagnosis. For all my slickness and knowledge, I hadn’t achieved the fundamental purpose of the examination.

It wasn’t that I hadn’t been spending time on the wards. I had been coming in every day, joining the ward round in the morning and helping with jobs in the afternoon.

The problem was: this isn’t a how you learn to recognise hepatomegaly.

The techniques described in Chapter 2 are great for the sit-down-and-study type of learning. Thankfully, not all of medicine is like that. We must also learn a whole host of ward-based skills, from taking blood to examining patients to working in a team. We must learn to appreciate the variation between individuals; how the same condition may present differently in two different people or how one patient wants all the details, and another only wants the key points. We must learn, for example, what is a normal-sized liver and what is hepatomegaly.

These are skills that can’t be learnt from a textbook. It won’t teach us to appreciate natural variation or how to respond to new situations. For this, we must spend time on the ward.

Yet it’s also possible to spend a lot of time on the wards without developing these skills much either. Some approaches are more effective than others. In this chapter I will explore how to make the most of time in clinical settings and how to deconstruct clinical skills in order to master them.

Making the most of clinical time

Unfortunately (for you), the clinical environment is designed to treat patients rather than to train medical students. This means it’s up to you to take the initiative. It is very easy to spend time on the ward, thinking that you’re a good student for being there, without learning very much at all.

To get the most out of your time, you should always have an objective, not be afraid to leave, tag onto good teachers and link your experiences to your reading.

Always have an objective

So much happens in a hospital on any given day. It’s easy to just go with the flow and hope that you passively absorb all the things you need to. With this approach you may have the occasional great clinical experience and will gradually pick up the required knowledge and skills with enough time. However, the more self-directed you are, the quicker you can learn and the better you can become.

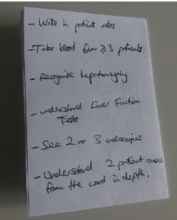

This is achieved by deciding your objective in advance. For me, this involved making a weekly priority list (during my weekly review, described in Chapter 2) as well as a daily objective list. At the end of each evening, I would take a piece of A4 paper and fold it in half three times. On this, I would write six things that I would like to achieve the following day, as in the example below. I would carry this in my pocket at all times, and cross things off when I achieved them, providing a small sense of achievement each time. Sometimes I would add a priority order by numbering them 1-6.

The six priorities in the above example are:

- Write in patient notes

- Take blood from ≥3 patients

- Recognise hepatomegaly

- Understand Liver Function Tests (LFTs)

- See 2 or 3 endoscopies

- Understand 2 patient’s cases from the ward in depth

This list can be tailored to the opportunities that you know you will have, for example if you know there is an endoscopy list tomorrow. When you write the objectives, you can think of ways you will achieve them. For example, for the list above you could plan to join the ward-round and ask to write in the patient notes (1) as well as choosing two interesting patients from the ward-round to study later (6). You could ask to leave the ward-round early to attend endoscopy (5), then after lunch come back to the ward and ask if there are any bloods to be taken (2), any patients to examine with signs (3) and if any of the doctors are free to explain LFTs (4). However, it’s important to be flexible as you can’t always predict how things will go. Maybe the doctors won’t let you write in the notes on the ward-round, or they are all too busy to teach you about LFTs. In these cases, you must be adaptable and seek alternative ways to achieve your aims, for example finding a guide on LFTs on the internet and then looking through the blood results of patients with deranged LFTs. Or maybe there are no patients in the hospital with hepatomegaly, in which case you can think of another sign you want to learn to recognise. It is on these days where having the objectives is so important, as otherwise you may spend a lot of time waiting around and achieve very little.

A great little book with suggestions for objectives is “101 things to do with spare moments on the ward” by Dason Evans and Nakul Patel. The title is self-explanatory.

Don’t be afraid to leave

That being said, there will be days where despite your objectives and your enthusiasm, there is just too little benefit to be gained from staying where you are. Perhaps the doctors are busy, you’ve seen all the patients with signs on examination and there’s not much else to do. Don’t feel an obligation to stay on the ward, in theatres or in clinics. Your time may be better spent elsewhere in the hospital or by going home and doing some study. If need be, excuse yourself with the phrase “I have teaching”. Don’t be afraid to attend multiple different theatres or clinics in the same morning or afternoon. It pays to have contingency plans in case a theatre case doesn’t happen or a doctor in clinic isn’t giving you any teaching.

Remember: you are not being paid and you are there for your own learning, so if you would learn more from leaving and doing something else then do so.

Tag on to good teachers

Sometimes you will have the good fortune of coming across a doctor who is (a) friendly, (b) keen to teach and (c) good at teaching. Tag on to them and milk them for all they are worth. Doctors who are good teachers can make a huge difference. As well as teaching you useful concepts, they can help direct your learning on the wards and get you involved with the team.

Newly qualified doctors (‘F1s’ in the UK) are often best as the content is still fresh in their minds and they may have more free time. However, a good registrar or consultant can provide greater depths of insight into their specialities.

If you want to be taught, make yourself teachable. Show enthusiasm and be proactive. Introduce yourself to the doctors. Ask questions when possible. Don’t be put off if someone blows you off (it’s not personal!).

One concern some students have is that they don’t want to distract doctors or waste their time. However, when doctors teach medical students it is mutually beneficial. Explaining things to you will refresh their memory of important content. I really enjoy teaching so when an enthusiastic medical student is on my ward it makes things much more enjoyable.

In Chapter 6 I shall make the case for why you should also get some teaching experience while at medical school.

Link your experiences to your reading

It is often better to learn the academic and clinical components of medicine together, rather than in isolation.

Aim to spend at least an hour each evening doing follow-up reading based on what you saw that day. For example, if you saw an interesting patient with jaundice, read further about the different causes of jaundice and how you can distinguish them.

Our brains have been shown to remember stories far better than abstract facts. In medicine, these ‘stories’ can be the stories of individual patients that you meet. By meeting a patient with a particular condition, you create mental ‘hooks’ for you to hang academic information off, which will make it far easier to remember. For example, a friend of mine met a patient with Fournier’s Gangrene in his fifth year and did some brief reading on it that evening. He never came across it again but during our final exams in sixth year, he remembered the patient he’d met and was able to answer a question on it. It is doubtful he would have remembered this had he either solely seen the patient or solely read about it in a textbook.

Linking patient experiences to reading can also be done on the ward by actively recalling your notes or previous knowledge when you see a patient with a particular condition. For example, if you meet a patient with Parkinson’s disease, and you previously made notes about the condition and different treatment methods, actively recall as much from your memory as you can. I often carry a rough piece of paper in my pocket, which I will occasionally take out and scribble on as much as I can remember on a topic. It can be useful to later refer to your notes to fill in any gaps.

Continued in Part 2.

status: No status —

This is a chapter from The Modern Medical Student Manual. A full list of chapters are below:

- Introduction: From That Day To This Book

- Chapter 1: Medicine from Fifty Thousand Feet: Perspective, Targets and Limits

- Chapter 2: The Fundamentals of Fast Learning - Part 1 and Part 2

- Chapter 3: Mastering Clinical Medicine - Part 1 and Part 2

- Chapter 4: Increasing our Impact (and the power of Self-Education) - Part 1 and Part 2

- Chapter 5: A Scientific Approach to Research - Part 1 and Part 2

- Chapter 6: Commanding Clearer Communication - Part 1 and Part 2

- Conclusion

Plus Bonus Chapters:

- Bonus Chapter 1: If Medicine Gets You Down

- Bonus Chapter 2: Is Medicine Right For Me?

- Bonus Chapter 3: Memorisation Techniques (by Dr James Hartley)

- Bonus Chapter 4: Learning from Others in Medicine