Increasing Your Impact (and the power of Self-Education) (Part 1)

“… And that’s why my friend quit medicine and became a banker.”

It wasn’t the conclusion I expected from a talk entitled ‘How doctors can do more good’, but I was intrigued.

I’d never really questioned the positive impact of doctors before then. I’d always thought it was a given that medicine is a great career because you save loads of lives. Yet this talk suggested that it wasn’t quite that simple.

Conventional wisdom is that the ultimate role of a doctor is to be as competent as possible. As long as a doctor is competent, they are doing a good job. While learning the academic and clinical aspects of medicine, as outlined in Chapters 2 and 3, are of fundamental importance, there are reasons why a doctor in the 21st century should be aiming to do much more than that. This chapter explores why and how.

Why should we do more?

Medicine = mostly algorithms

There are optimum algorithms to follow in almost all situations, as determined by the existing evidence base and ‘best practice’. It is how well a doctor follows these algorithms which determines the impact they have in their clinical practice. Skills such as communication and teamwork are important but their impact may be less direct.

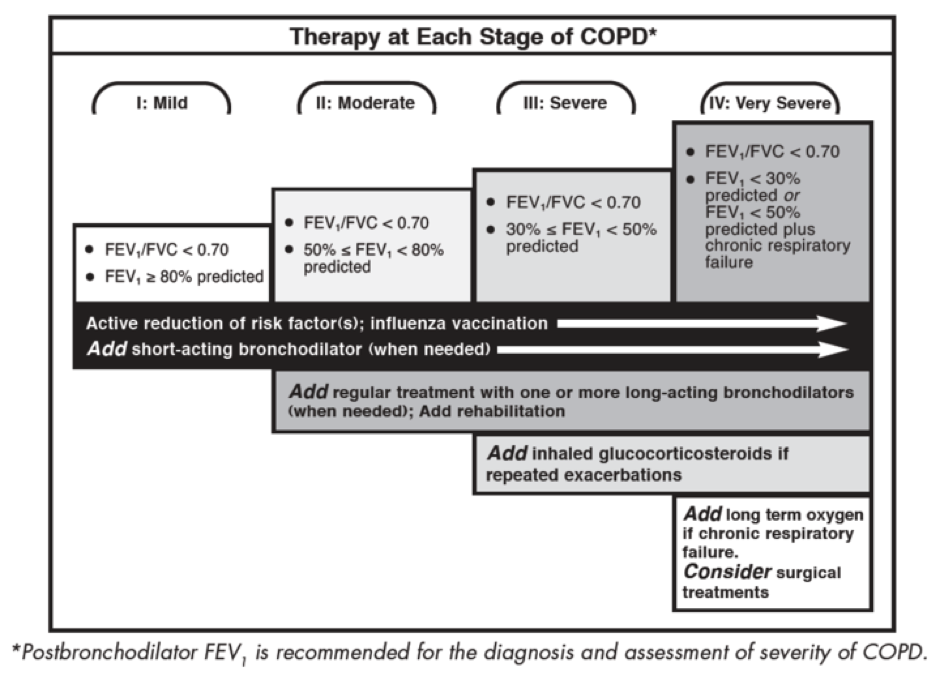

Becoming a better medical student and doctor involves becoming better at these algorithms. Early on we learn the algorithms for taking a history and doing examinations. We learn the algorithms for treating different conditions. Examples include the ‘Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS) protocol’ for the immediate response to a heart attack or the ‘GOLD guidelines’ for long-term management of COPD.

Diminishing returns

Ongoing medical training is aimed at increasing the ability to follow these algorithms. More skilled doctors are able to follow them more consistently and more quickly. They also have a greater appreciation of the intricacies of the algorithms.

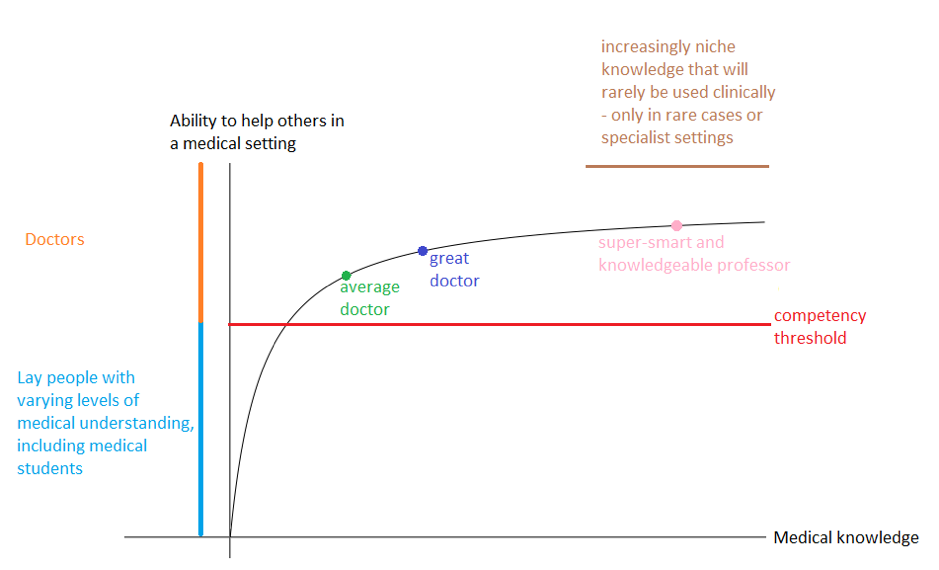

All medically-qualified doctors are, by definition, considered competent. They are deemed good enough at following the required protocols in order treat their patients.

The benefits of exerting effort to further exceed this ‘competency threshold’ are subject to the law of diminishing returns, as shown below.

Greater understanding of medicine beyond what is required for competency does not lead to a significantly better impact on patients for a number of reasons:

There is extensive guidance on the different algorithms to follow, including NICE guidelines, trust guidelines and other resources. If you are unsure of an action, more often than not specific guidelines will exist that you can follow.

Greater knowledge doesn’t necessarily lead to better action. For example, someone may know that NSAIDs should not be used in a patient with asthma because inhibiting COX enzymes leads to an increase in leukotriene levels which exacerbates asthma. However, another person can know only ‘don’t use NSAIDs in asthma’ and will still be able to take the same action.

As a junior doctor, you can consult senior doctors if unsure. If a decision is outside of your scope, a senior or a specialist will be able to help.

As a senior doctor, you can consult people with more specialist experience. When something falls outside of your clinical comfort zone, there are other doctors with more experience in that particular area that can help.

Treating the patients you meet

The benefits of the competent-to-excellent progression faces a further restriction; you can only treat the patients directly in front of you. You are only one individual so no matter how much better you may be than your peers at clinical medicine, only the patients fortunate enough to interact with you directly will benefit from this.

This is not the case in other fields or professions. For example, consider the public health researcher who devises a scheme that lowers the national smoking rate or the researcher who contributes to the discovery of a new anti-cancer drug. Even a relatively tiny contribution can lead to greater overall benefits due to the ability to scale up. For a population of 50,000, would you rather have 1 amazing doctor or 100 average doctors? How about 1 amazing scientist or 100 average scientists? These answers are different for a reason.

Therefore, the doctors who make the greatest positive contribution to the health of a population do so through things which can scale-up and affect more people. There are approaches that can be taken at medical school to maximise our ability of doing so.

How can we increase our impact?

In the talk referenced at the start of this chapter, entitled ‘How doctors can do more good’, Dr Gregory Lewis presented evidence suggesting that a banker giving away 10% of his earnings to cost-effective charities will save more lives (measured as QALYs or Quality-Adjusted Life Years) than the average doctor. (Of course, the average banker doesn’t give away 10% of his earnings to charity.)

In this book I will explore instead how we can increase our positive impact directly through our work. For those interested in Dr Lewis’ work, he explains the research in depth on the 80,000 Hours blog: https://80000hours.org/2012/08/how-many-lives-does-a-doctor-save/

Extending our work beyond our direct clinical practice can dramatically enhance our positive impact. Doing so requires motivation so it needs to be something that we enjoy. Therefore, one of the best ways to maximise our contribution to the medical field is to find something we love doing and work out how to use it to make a positive impact.

Based on our unique combination of genetic make-up and personal experiences there are certain areas we are predisposed to enjoy and excel in. However, discovering these areas can involve a lot of hard work. Cal Newport is a computer science professor who researched the pursuit of fulfilling work. He found that you must develop a sufficient level of skill and insight to know whether you deeply enjoy an area. This requires a sustained period of hard work.

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to finding what we love. It often involves a wide exploration and a lot of trial-and-error. However, two principles that can facilitate it are undertaking extensive self-education and developing fundamental transferrable skills. I shall explore these principles in this chapter as well as Chapters 5 and 6.

Medical school provides a great opportunity to do so. We have more free time, fewer real-life commitments and more opportunities for experimentation.

The benefits of extending our work

Finding work you love can provide you with immense satisfaction as well as maximise the impact you have.

In the short-term, pleasure and drive gained from working hard towards something you love has knock-on effects in other areas of your life. By increasing your mood and your drive it can lead to better performance in clinical practice. It also gives you motivation to study efficiently to make more time for what you love.

In the long-term, the greater levels of skill and understanding that can be attained will maximise your ability to make a positive impact on the medical field. You may think of improvements or find solutions that have never been found before. The ways that this can be done are extremely broad so I will demonstrate with some examples. These are far from comprehensive.

Incorporating our passion into medicine

Some people will find deep interest in areas that can combine with medicine quite naturally, enabling them to have a positive impact.

Mr Samer Nashef is a prominent cardiac surgeon who combined an interest in statistics with his medical expertise to create a risk model for cardiac surgery called the EuroSCORE. This has been implemented world-wide and can be credited with saving millions of lives by improving success rates and reducing unnecessary surgery.

Mr Shafi Ahmed is a surgeon who is interested in novel technology and in medical education. He combined these interests by live-streaming operations by wearing special glasses which record what he can see. He gave teaching while conducting these operations and they have been watched by thousands in the comfort of their own homes. He has founded Medical Realities which uses virtual reality and augmented reality to improve surgical training.

For others, the potential for combination may not be as obvious.

Mandeep Singh is a medical student whose passion is learning to rap. For a long time, medicine and rap were two very separate parts of his life. Then he decided to use rapping as a medium to help patients and to improve healthcare. One way is to tell stories which can help patients process certain emotions and psychological problems. He played me one of his raps describing the experiences of a patient he’d met, and it almost brought me to tears. He has written an insightful account of principles for developing mastery in rap but which are transferrable to other areas also: accessible here.

When exploring personal interests, try to avoid filtering things out based on how easily they may be applied to medicine. It’s better to explore things you are more genuinely passionate about, even if you have to work harder to incorporate it into medicine at a later date. Sometimes the potential for combining interests will not be obvious until higher levels of mastery are obtained.

It is possible, however, that you may find a passion in something that you deem incompatible with medicine. While you may be content to keep it as a hobby, the enjoyment may drive you to make it a bigger feature of your life. This presents you with a tough decision. It may be that medicine prevents you from doing the things that provide the deepest enjoyment and satisfaction. If this is case, then the right decision may be to follow your passion rather than stay in medicine wishing you were elsewhere. If you ever question whether medicine is right for you, I consider this question in greater depth in the Bonus Chapter.

There is no way to guarantee that you will find work you love. Everyone’s path in life is different. However, two fundamental things that can enable you to discover deeper levels of enjoyment and satisfaction are self-education, which I will explore now, and developing fundamental transferrable skills, which I will explore in Chapters 5 and 6.

Continued in Part 2.

status: No status —

This is a chapter from The Modern Medical Student Manual. A full list of chapters are below:

- Introduction: From That Day To This Book

- Chapter 1: Medicine from Fifty Thousand Feet: Perspective, Targets and Limits

- Chapter 2: The Fundamentals of Fast Learning - Part 1 and Part 2

- Chapter 3: Mastering Clinical Medicine - Part 1 and Part 2

- Chapter 4: Increasing our Impact (and the power of Self-Education) - Part 1 and Part 2

- Chapter 5: A Scientific Approach to Research - Part 1 and Part 2

- Chapter 6: Commanding Clearer Communication - Part 1 and Part 2

- Conclusion

Plus Bonus Chapters:

- Bonus Chapter 1: If Medicine Gets You Down

- Bonus Chapter 2: Is Medicine Right For Me?

- Bonus Chapter 3: Memorisation Techniques (by Dr James Hartley)

- Bonus Chapter 4: Learning from Others in Medicine