A Scientific Approach to Research (Part 1) - The Idea

I turned off my computer, flicked the light switch and climbed into bed. I was bored and exhausted.

I’d used up all my motivational reserves over the last three hours, trudging through excel data on my computer. I didn’t even see why this project was important. It wasn’t clear to me how it would help anyone, patients or doctors.

‘Well, at least I’ll get a paper published’, I thought.

A long story, short: that paper was never published. Bummer.

Fast-forward two years and the enthusiasm with which I clicked the ‘Submit’ button was almost palpable.

I’d spent far more late nights on this project than the first one, but I didn’t mind.

Three weeks later, when I received the email that began “It is a pleasure to accept your manuscript in its current form”, I pumped my fists into the air with jubilation.

Medical school offers many opportunities to get involved in research. You can do it alongside placements or during your holidays.

Should you get involved in research? What’s the best approach? Let’s explore the answers to these questions.

Do your own work

Learning to think for yourself is one of the most valuable skills you can develop. Scientific research can be a great arena for developing this ability but only if the right approach is taken. It can also directly help your medical career as published scientific papers strengthen future job applications and can help you to establish connections.

Progress in scientific understanding is fuelled by new ideas. Those that contribute most to science are those with the ability to think most clearly to come up with new ideas. We often create an us-them distinction between ‘geniuses’ who come up with great ideas and the ‘normal’ rest of us who can only marvel at them. Yet this ability can be improved by taking an intelligent approach for a sustained period. The approach to self-education described in Chapter 4 and the learning for understanding principle outlined in Chapter 2 can be a part of this development.

The most common approach to scientific research as a student does little to foster this ability. It involves taking on a pre-formed project from a senior doctor or researcher and giving up your time to do the boring parts of the project. By crunching the numbers or sifting through the data, you will get your name on the final paper.

However, you gain little else as the ‘higher thinking’ parts of the project (conception, study design and analysis) have already been completed. At most, you will gain some insight into the thought process of the actual scientist behind the study and it may also stimulate some thought of your own regarding other possible projects or ways the data may be interpreted. It is a very inefficient way to develop the ability to think well and involves giving away valuable free time purely for CV points. This may only be justified if you are applying for a super-competitive specialty and need your name on as many papers as possible. Even then, it may become more efficient to conceive ideas and have someone else do the leg-work once you have developed your ability to think of good project ideas.

In short, the approach to take is think of your project idea first and then find the most suitable supervisor based on the idea.

The idea

We must learn to think for ourselves and train our brains to come up with good ideas. Active brainstorming is to our brains what regular exercise is to our bodies. Below I’ve outlined a useful approach to brainstorming. However, while the technique is simple and effective, the act of doing so regularly can be challenging.

One reason is that we typically don’t value our ideas highly enough. When confronted with a problem, many seek someone else to provide us with an answer. Another is the discipline it takes. Trying to think deeply on any subject strains our brains and it can be frustrating if we don’t see early positive results. The easy route out is to distract ourselves or let our minds wander. It is only through continuous trial and error that our thinking ability will improve.

In combination, these issues may prevent us from trying to think deeply in order to solve problems. Without practice, our ideas may not be good so we take the answers from others and thus never get the practice required.

One idea can change the world. Every Nobel Prize started out as an idea. To give ourselves the best chance of coming up with ideas that will improve our lives and the lives of those around us, we must train our brains to do so. Actively brainstorming is a way to start this process. In his book Deep Work, Cal Newport explains ways to go further.

If you are interested in the principles behind thinking for ourselves and improving the world, Tim Urban has written an excellent piece using Elon Musk to demonstrate how to do so and addressing the issues of pride, fear and the influence of society: https://waitbutwhy.com/2015/11/the-cook-and-the-chef-musks-secret-sauce.html

Active brainstorming

1. Create the right environment

Block out a period of at least an hour. Remove all distractions during this time. For me, this means phone in another room, computer switched off and ensuring I won’t be interrupted by friends.

2. Get ready

Sit down with a sheet of paper, a pen and nothing else. In theory, a computer, phone or tablet would be fine to write on but make sure you won’t get any notifications or other distractions. Decide the topic or question that you will brainstorm on.

3. Think of as many ideas as possible

As soon as you think of an idea, write it down. It doesn’t matter if you feel it’s terrible. Any bad idea may lead to a good idea plus no-one else is going to read it (unless you take a photo of it and put it in a book…). Don’t try to filter your ideas at this stage as it will disrupt your creative flow.

If the ideas don’t come easily, persevere. Don’t allow yourself to get distracted or quit. It’s easy to give up when you feel resistance but commit to at least one hour focussed on the task.

If the ideas do start to flow, keep asking follow-up questions, considering different variations or combinations of the ideas you come up with.

4. Filter the ideas

Once you have exhausted all lines of exploration or are feeling mentally ‘spent’, it’s time to go back and assess what you’ve come up with. Which ideas have the greatest potential? If you could only keep three, which would they be? Which ideas seem bad at first glance but may be modified in some way? You can brainstorm further if new ideas start to form.

5. Test the ideas

Discuss the idea with a friend who will ask you probing questions. Practise articulating the concept so you know exactly what it is that you’ve come up with. A friend may highlight positive or negative aspects that you didn’t think of.

Search the internet to see if anyone has had this idea before or anything similar. Part of you may not want to know if it already exists but make sure your search is thorough. You don’t want to put in work only to later realise it has already been done. However, if you see something similar don’t readily dismiss your idea as there may be a fundamental distinction.

For a scientific research project idea, undertake an extensive literature search. Use PubMed to do a focussed search of existing studies in a similar manner to above. Having seen what other people have done, what new ideas can you think of related to your idea or theirs?

If your idea is for an entrepreneurial pursuit, Josh Kaufman has provided an excellent checklist of “Ten Ways to Evaluate a Market” which are available here: https://personalmba.com/10-ways-to-evaluate-a-market/.

Note: The main limitation is not finding the time to do this. Put this book down right now and have a brainstorm. Remove distractions, grab some paper, decide an area of medicine you want to think about and give it a go!

I’d be interested to hear about any benefit you get from this method or any new ideas you come up with. I’m also happy to be the friend who objectively assesses your idea. Drop me an email and I’ll help in any way I can: chris@medicalstudentmanual.com.

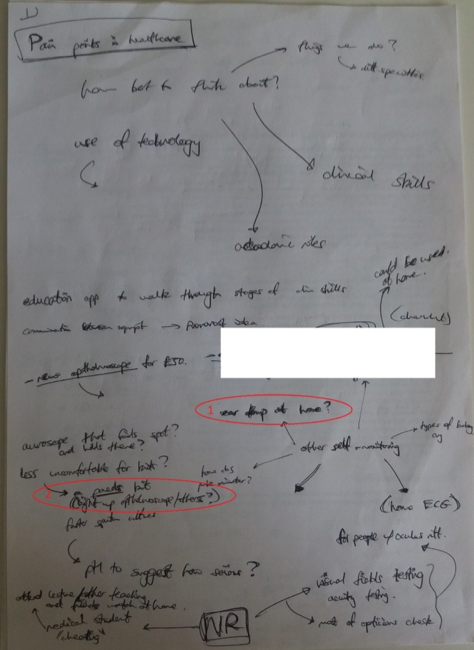

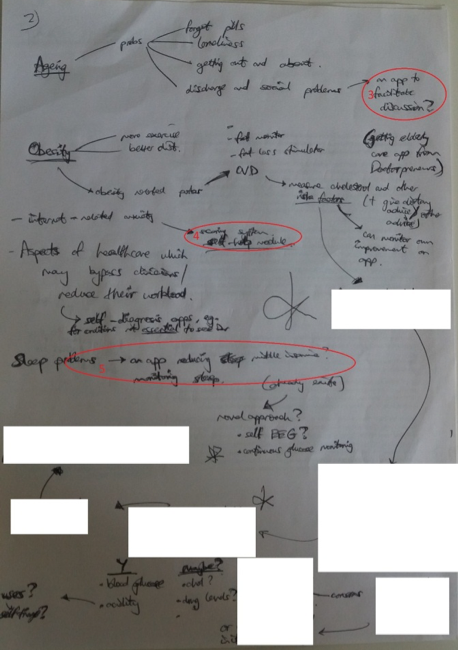

Pain points in healthcare

For example, one evening I brainstormed on ‘Pain points in healthcare’. I have attached images of the original notes below. (Excuse the bad handwriting… doctor in training.)

Most of the routes of exploration did not produce anything of value. However, from this brainstorm I came up with two good ideas which myself and a colleague worked on.

In the process of finding these two good ideas, there were many bad ideas and failed routes of inquiry. These is just part of the process. I have circled them in red and explained why they are bad ideas below.

Bad ideas:

- Measuring temperature at home via the ear: parents already often measure their children’s temperatures when they get ill.

- A stethoscope that lights up or makes sounds to distract babies: adding lights or sounds to a stethoscope would be highly impractical and offers little benefit on top of having a stethoscope and a toy that lights up or makes sounds separately.

- Creating an app to facilitate discharge discussion would be highly challenging and not possible for someone who isn’t already well-integrated in healthcare management.

- CBT self-help modules for anxiety already exist.

- Apps that monitor sleep quality already exist.

Continued in Part 2.

status: No status —

This is a chapter from The Modern Medical Student Manual. A full list of chapters are below:

- Introduction: From That Day To This Book

- Chapter 1: Medicine from Fifty Thousand Feet: Perspective, Targets and Limits

- Chapter 2: The Fundamentals of Fast Learning - Part 1 and Part 2

- Chapter 3: Mastering Clinical Medicine - Part 1 and Part 2

- Chapter 4: Increasing our Impact (and the power of Self-Education) - Part 1 and Part 2

- Chapter 5: A Scientific Approach to Research - Part 1 and Part 2

- Chapter 6: Commanding Clearer Communication - Part 1 and Part 2

- Conclusion

Plus Bonus Chapters:

- Bonus Chapter 1: If Medicine Gets You Down

- Bonus Chapter 2: Is Medicine Right For Me?

- Bonus Chapter 3: Memorisation Techniques (by Dr James Hartley)

- Bonus Chapter 4: Learning from Others in Medicine