The Sour Lesson: A Guide to Building AGI-Pilled Products

With the current rate of AI progress, every AI product builder must confront an uncomfortable question: How should I build my product when my approach could become obsolete with the next model release?

You need to serve customers today so you have to ship something using current capabilities - but those capabilities will change. Build too specifically around those limitations and you create technical debt. Build too generally for tomorrow, and you can’t ship anything useful.

I’ve seen this play out repeatedly over the last 3+ years building LLM-powered products at the frontier, at Anterior (automating healthcare administration) and elsewhere. Some approaches stand the test of time, while others don’t.

The “Sour Lesson” of Building AI Products

Richard Sutton’s Bitter Lesson points out that in machine learning, methods that simply scale data and computation for learning and search have consistently won out in the long run against approaches that have tried to bake-in human expertise (even if the latter initially performs better).

While Sutton is talking about the model layer; how to train better AI systems. I want to propose a corollary for the application layer; how to build products on top of those systems. Let’s call it the “Sour Lesson”:

The product approaches that win are those which compound with model progress rather than compete with it.

(And approaches that specifically work around current model limitations will age like grapes in the sun - and become sour.. 🥲)

Defining this is the easy part. The hard part is (i) building an intuition for what those approaches are and then (ii) leveraging that intuition to build ‘Sour Lesson-pilled’ products.

In this essay, I’ll share:

- Real examples from the last 3 years showing which approaches aged well and which went sour (and why)

- The Sour Lesson Scorecard - a framework for deciding which product bets will compound with AI progress

- How to build a Sour Lesson-Pilled organization

When Solutions Went Sour

Hierarchical Query Reasoning

The Context: In the summer of 2023, I was building our first product for performing medical reviews, powered by GPT-3.5-Turbo-16k. A typical medical review requires processing:

- Clinical guidelines (often 20-50 pages, and with complex nested logic - see example)

- Patient medical records (can be 100+ pages)

16K tokens wasn’t enough to reason over all of this at once.

What We Did: I created a technique (which I referred to as ‘hierarchical query reasoning’) which broke guideline documents into tree-structured questions where high-level guideline requirements decomposed into more specific sub-questions, each answerable within the token limit.

The system would:

- Parse guidelines into a tree of dependent questions, from high-level requirements down to specific clinical criteria

- Answer each question separately against the medical record, starting with leaf nodes and working up the tree

- Propagate answers up through parent nodes to make a final determination

How it played out: In November 2023, GPT-4 Turbo launched with a 128K context window. Suddenly we could reason over the entire case at once. The deconstructed approach wasn’t just unnecessary, it was actually limiting us. Parallel reasoning became possible, which was faster and often more accurate.

The whole thing took 1-2 months and landed us our first 2 enterprise customers, so no regrets. But within 6 months, we’d moved on to a different approach entirely.

Finetuning for Clinical Reasoning

The Context: In 2023, the prevailing wisdom was that for specialized domains like healthcare, you need finetuned models to achieve strong reasoning performance. General models wouldn’t be good enough at clinical reasoning.

What We Did: I hired clinicians and built clinical reasoning datasets. I finetuned models to improve medical reasoning quality and to control output formatting.

How it played out: Within 12-18 months, general models (GPT-4, Claude 3, etc.) became so good at clinical reasoning that more specialized models offered no advantage. The frontier models were trained on enough medical literature, research, and clinical data that their medical reasoning capabilities were strong - and not the limitation on our product’s performance.

It’s now clear that prompting techniques should be the first point-of-call for improving performance, even in specialized verticals, and I’ve spoken more about this here. But it wasn’t obvious at the time (at least to me) that this was going to be the case.

Solutions That Aged Like Wine

Not everything became obsolete. Some ideas I had 2+ years ago are still in production. What made the difference?

Domain Knowledge Injection

The Context: I noticed our product was often not appreciating context-specific nuance. When deploying in enterprise, there’s a lot of tacit knowledge within each company that the models won’t appreciate. There’s also variation in how terms can be interpreted. For example, the term “conservative therapy” means something different in a surgical context vs a medical context.

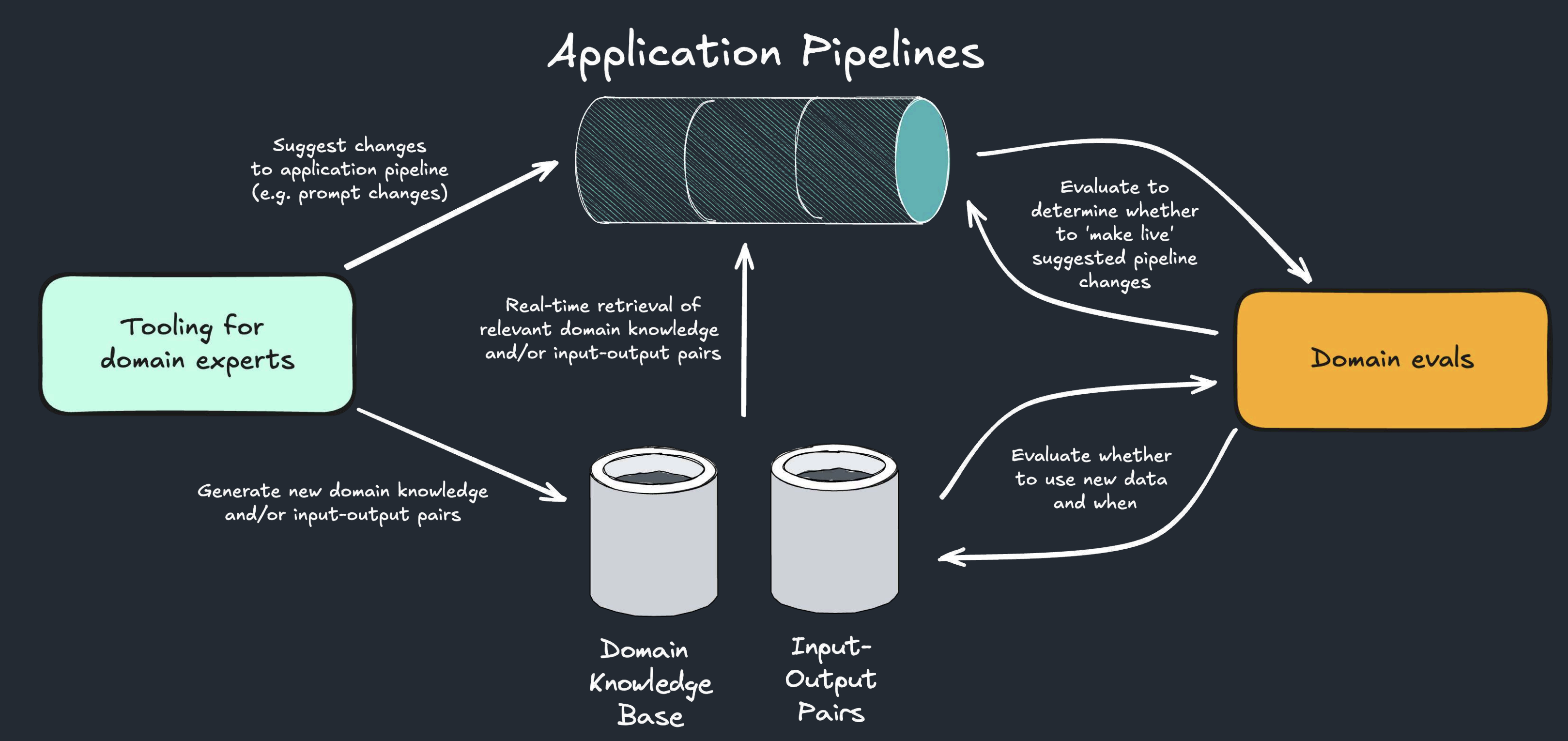

What We Did: I proposed building a scalable library of clinical knowledge which is dynamically injected at inference time based on the context the model is operating within.

How it played out: This approach is still in production 2+ years later, and it’s a key mechanism by which we solve the “last mile problem” on a customer-specific basis (which I spoke more about here).

It survived because this approach doesn’t depend on specific model capabilities and its utility actually scales with model improvements. As context windows increase, you can just provide more of this clinical domain knowledge into the context. As you collect more performance data, you can better select the domain knowledge that improves performance in different contexts (meaning the knowledge base itself can keep scaling - practically infinitely).

Leveraging Domain Expert Reviews

The Context: When I was first building the product, I could check the AI outputs myself (I’m a qualified medical doctor) then use what I saw to make changes to the product. However, this doesn’t scale - we needed a way to capture domain expert insight as data and use it to improve the product.

What We Did: I built a dashboard to enable domain experts (clinicians) to perform reviews (more info here) and designed a system downstream that used the data we get from reviews in various ways:

- Provide performance metrics that we can use to prioritize improvement work

- Identify and classify ‘failure modes’ (the ways in which our AI was making mistakes) to help identify how we can fix it

- Generating suggested domain knowledge injections

- Generate example input-output pairs for in-context learning

How it played out: This remains a key component of how our product works today - for reporting performance to customers, for speeding up AI iteration and for improving performance. The data generated by these reviews is a core part of the technical moat for the company. Performing more clinician reviews directly translates into a better and more differentiated product.

What does this tell us and what should we do?

The most obvious theme is that the approaches which survived focussed on overcoming limitations of applying LLMs that are not inherent to the LLMs themselves. For example, both the surviving techniques could be categorized as “context engineering”; getting more relevant and detailed context to the LLM, rather than trying to improve how the LLM leverages that context.

Whether these same techniques continue to be helpful going forward is yet to be seen. Perhaps in an agentic AI world, the models will just go and get the context that they need, without the need for you to engineer the context for them at all.

But my point is: we don’t know for certain what the future will look like and therefore we’re forced to make educated guesses. Here’s a framework for doing so:

The Sour Lesson Scorecard

- List out:

- all limitations and assumptions around the current capabilities of models

- all relevant new capabilities that new approaches or alternative models might provide in future

- Brainstorm and map out all the potential approaches you could work on for improving your product

- Plot a matrix with limitations and assumptions against your potential approaches.

- For each square, label whether this limitation becoming untrue or this new capability becoming true makes your approach more relevant, less relevant, or has no impact (and why)

You’ll end up with something like the following:

| Approach | Context Window Expansion | Improved Domain Reasoning | Better Multimodal | Understanding Workflows/Last Mile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hierarchical Query Reasoning | ❌ Less relevant - can process entire case at once, making decomposition unnecessary | ❌ Less relevant - better reasoning reduces need for structured breakdown | → No major impact | → No major impact |

| Finetuning for Clinical Reasoning | → No major impact | ❌ Less relevant - general models become good enough at clinical reasoning | → No major impact | → No major impact |

| Domain Knowledge Injection | ✅ More relevant - can inject more tips as context grows | ✅ More relevant - better models use tips more effectively | ✅ More relevant - can include visual/multimodal domain knowledge | ✅ More relevant - can capture workflow-specific nuance |

| Expert Review System | → No major impact | ✅ More relevant - generates training data that compounds with better models | ✅ More relevant - can capture multimodal feedback | ✅ More relevant - directly captures last-mile workflow issues |

You can then use this to inform your decision-making around priorities and allocation of effort.

Just because something might become redundant doesn’t mean you shouldn’t do it. Maybe it helps you serve your customers better for the next 6 months (like my ‘hierarchical query reasoning’ example) and that makes a meaningful difference to your company’s trajectory. Or maybe you have limited resources and want to go all in on one approach you’re convinced will win in the long run. Making your hypotheses explicit helps you consider these trade-offs.

A Sour Lesson-Pilled Organization

There are also approaches you can take at an organizational level to make yourself more ‘Sour Lesson pilled’.

I’ve seen companies be explicit about the proportion of time and resource they want to allocate to optimizing the current product vs. testing new approaches. I’ve advocated for a rough 70%:30% split at organizations where I’ve worked, which feels about right - but depending on the nature of your product and risk tolerance you could spend more time on experimentation.

There are two ways to enact this in practice; at the level of engineers (asking some engineers to work on optimization and others to purely do experimentation) or at the level of workflow (all engineers do a mix of both). I’d advocate for the latter, as you don’t want your ‘experimental’ engineers to have some anchoring in today’s state-of-play.

In general, a culture of experimentation is key; in which some engineer-driven exploratory work, that may or may not materialize as concrete outputs, is not penalized. E.g., At Anterior, I set up a monthly internal hackathon called “Anterior Labs”, with the explicit mandate of trying to disrupt our current approach. We’d list out all the new models, capabilities, tools, etc from the last month, then different teams would grab them and experiment. This was highly successful; almost every session we did yielded new ideas that ultimately ended up within our main product (from a new approach to ingesting PDFs to our first long-context model implementation of reasoning).

Set up your codebase to make experimentation cheap. Build modular architectures where you can swap components easily. This lets you test whether a new approach actually improves things before committing to it. Keep coupling low so you can replace entire subsystems when better capabilities emerge. And critically: be willing to delete code you’ve invested in. The real sunk cost is maintaining an approach that’s been superseded, not the time you spent building it.

In Conclusion

As models keep getting better, the companies that survive will be the ones that grow with model progress rather than those made redundant by it. The fundamental challenge hasn’t changed: you still need to ship products today that serve customers now, even as the landscape shifts beneath you every few months. But you can navigate this tension by building an intuition for approaches that compound with progress, being explicit about the hypotheses you’re betting on, and internalizing the Sour Lesson. The goal isn’t to predict the future perfectly - it’s to build in a way that benefits from it rather than fights against it.

Comments powered by Disqus.