What will British healthcare look like in 20 years' time?

At 8:40am, a medical student named Derek entered the doctor’s office on the Enhanced Recovery post-op ward and sat down by a computer. Two of the foundation doctors, Amir and Sarah, looked up to acknowledge his presence before continuing their preparation for the imminent ward-round.

Derek was feeling pro-active so he grabbed the office’s VR headset and looked up which operations were currently being streamed. To his delight, a patient undergoing a spinal reconnection had consented for educational streaming and the operation had started 40 minutes ago. Derek promptly re-winded to the start of the operation then skimmed through, stopping briefly to watch the sural nerve harvest, until he was watching in real-time. He had read about this operation recently; he knew that the surgeon would now inject cultured olfactory bulb cells into the spinal cord above and below the lesion that had just been bridged by the sural nerve. As the surgeon prepared to do so, Derek submitted a question about the depth and angle of injection. He was pleased to see it received a few early upvotes from fellow viewers. It consequently appeared on the surgeon’s headset, who promptly answered it out-loud as he prepared the injection.

As he was watching the injections, he felt a tap on the shoulder and removed the headset to find the room was now full of doctors and handover was about to begin. He listened attentively as the new admissions were recounted by the on-call doctor and then the ward-round got under way.

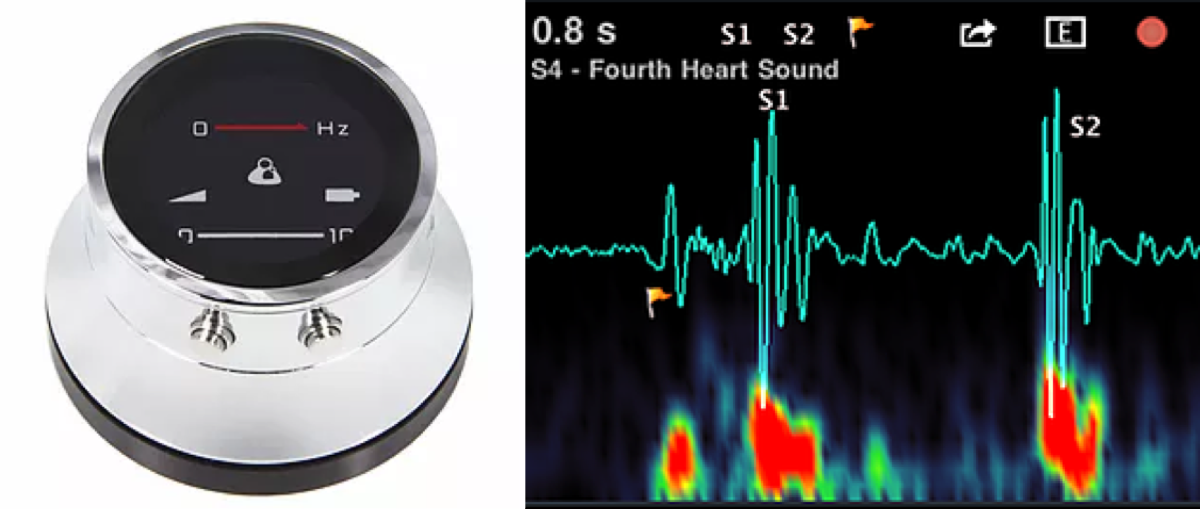

The first patient, Mr Powell, was a 78-year-old gentlemen who had undergone a valve-in-valve transcatheter aortic valve implantation (ViV-TAVI) the previous day. His original TAVI from 14 years prior had begun to leak, warranting the insertion of a second, slightly smaller aortic valve within the first. The consultant placed his electronic stethoscope head on the aortic region of the patient’s chest and stepped back to analyse the reading on the computer. It displayed the S1 and S2 heart sound waveforms, as well as a faint diastolic murmur, and computed the estimated functional improvement.

As Mr Powell was medically fit for discharge, they just needed to ensure that his Shared Care Plan had been approved by all parties. They checked on the computer – the GP had seen and approved it that morning but they were just waiting on the allocated district nurse, who was scheduled to review it later that morning.

“If all goes according to plan, Mr Powell, you’ll be home by lunchtime” the consultant commented, cheerily, and the team left the bay.

“The next patient has dementia”, the consultant commented, turning to Derek, “what strategies do you know about in the community to help him?”

“As a recently-certified ‘Dementia-Friendly Community’, the Cambridge area has successfully implemented a number of schemes, from public transport services that help people get on and off at the right stops to dementia-friendly supermarkets with regular maps and sign-posting as well as trained staff,” Derek replied.

Amir’s bleep went off. It was an automated message from EPIC, so he pressed a button on his earpiece: “This is the EPIC Early-Warning System. Based on the latest pattern of blood results for Mrs Esquire on Dover Ward, there is a 56% probability of her developing sepsis within the next 24 hours. Please attend to her as soon as possible.”

Derek shadowed Amir for the rest of the morning.

At lunch, Derek planned his afternoon. He checked the ‘Patients for Students’ list on his phone and saw that a lady was coming in for removal of a malignant melanoma. He’d read about these in textbooks but since the Early Detection Program was implemented in supermarkets it was rare to see them beyond an early stage. Many supermarkets were now offering bonus club card points for people who regularly got themselves checked out by stepping into one of the booths by the check-out machines.

He had a gap between the operation and a history-taking chat bot session, so opened another app to arrange a teaching session. He saw that an F1 on HPB was expecting a quiet afternoon, so requested a teaching session on liver function tests – his request was later accepted and two other medical students signed up to also join.

After the operation and teaching, Derek spent an hour in a booth in the library taking histories from different chat bot personalities with various complaints and receiving tailored feedback. He then headed home, opened up ‘Dr’s Assistant’ on his computer and recounted what he had seen that day. The software used this recollection, plus data from his past records of study, projections for future assessments and a spaced repetition-based algorithm to present him with relevant learning material and questions to conclude his day.

This article was runner-up in the Cambridge Medical Journal essay competition 2017. Originally published on 11th July 2017, available here.

Comments powered by Disqus.