The Truth Is In The Title? Video Title Generation as a novel training objective for video summarisation

Abstract

We propose the task of video title generation (VTG) and present the YouTube Titles and Transcripts (YTT) dataset which consists of 17,886 video titles and accompanying transcripts. We approach the problem both as a forward-predictive task and as a summarisation task and explore a number of methods for pre-processing the video transcripts to extract pertinent information. Our human evaluation found that titles generated using a forward predictive approach were more succinct and in some cases more informative than the ground truth titles. Generating video titles could have real-world utility, to support information extraction from video content: both by consumers and by algorithms.

Download a PDF version of this article here.

Access the dataset generated for this work here.

Introduction

The volume of video content on the internet is increasing exponentially. 80% of the world’s internet traffic is projected to be video content1, with 720,000 hours uploaded2 and 1 billion hours watched3 every day on YouTube alone. Yet filtering signal from noise can be challenging. Videos are inherently less ‘skimmable’ than written content and present novel challenges for search algorithms.

For videos composed predominantly of speech, natural language processing (NLP) could provide the means to extract information for computational analysis. However, NLP research to-date has centred around written text and the spoken word presents additional challenges. For example, it doesn’t conform to the same grammatical rules as written text. This is because spoken word has a more continuous, spontaneous flow, and often contains more filler words.

It has also been previously noted that there is a paucity of human-annotated data for text from videos4. In this paper, however, we propose a novel formulation which overcomes this problem: Video Title Generation (VTG). Viewed as an abstractive summarisation task, the user-generated video titles can become the ground truth summaries of the full video transcripts. This yields a large, readily-available and ever-expanding dataset.

Doing so, however, is a challenging task. Video titles are short, so generating them requires an algorithm to significantly compress long passages of speech. Human-generated titles don’t follow strict naming conventions. Additionally, incentives may not be aligned; titles with higher ‘click-ability’ may generate more revenue, and thus be given higher preference than more accurate ones.

The ability to accurately generate titles could have many real-world applications, such as improving video search engines, supporting content moderation and facilitating information extraction for further analysis. Such a tool could support consumers of video content; titles that factually describe the core content of a video may better support user decisions than human-generated titles. Such algorithms may also be extended to generate longer summaries of video content, broadening the scope of its utility. For these reasons, we believe this problem is of interest to the research community and wider society.

The contributions of this paper can be summarised as follows:

- We propose the task of Video Title Generation (VTG) and publish the YouTube Titles and Transcripts (YTT) dataset; the first large-scale dataset of human-generated transcripts and video titles.

- We show that VTG is best approached as a forward-predictive task, where models generate titles token-by-token based on the transcript

- We propose a modelling pipeline centred around fine-tuning GPT-2, with preference placed on the start and end of video transcripts.

- We demonstrate this model can generate titles which are typically more succinct and sometimes deemed superior to human-generated titles.

Our Hypotheses

The hypotheses motivating this study were the following:

- State-of-the-art pre-trained language models can be fine-tuned to create human-level video titles.

- Such titles may be better factual descriptions of the video content, overcoming bias towards ‘click-ability’ that may exist in human-generated titles.

- Two well-suited models for this task are PEGASUS and GPT-2. PEGASUS is trained with a ‘gap sentence generation’ objective5, which is similar to generating sentence-length video titles. GPT-2 has achieved SOTA performance in a wide range of text generation domains6.

- The length of transcripts will be a key challenge. Using extractive summarisation methods to shorten them will improve performance.

- The most important portions of the transcript are the start, then the end, followed by the rest of the transcript.

Related Work

Existing work for summarising video content has centred on generating captions from important video frames and combining them using natural language processing techniques7. This requires heavily-curated datasets and is limited by the quality of caption generation.

An alternative approach, of using video transcripts to generate summaries, has not been explored until recently. To our knowledge, only one such study, by4, has done so.

However, this approach falls within the broader task of text summarisation, which is a mature research field dating back as early as the 1950s8.

Title generation is a special case of text summarisation

The central aim of summarisation is to create a compressed natural language representation of the main ideas presented within some text9. Headline generation is a special type of document summarisation, where the generated natural language summaries are limited to one sentence in length10. Thus, our proposed task of Video Title Generation can be considered the analogue of headline generation for video data.

This constraint on length provides a significant added challenge, particularly as the document length increases, and previous work has highlighted that small grammatical or factual errors can make generated titles essentially useless11121314. Performing well, therefore, requires a strong language understanding.

Early research for headline generation utilised handcrafted features with rule-based15, compression-based1617 and statistical-based methods1018. Since then, recurrent neural networks19 and attention mechanisms202122 have been explored.

Extractive and abstractive summarisation

Summarisation approaches can be broadly grouped into extractive and abstractive methods. Extractive summarisation aims to select the most important spans of text from within a document and combine them to generate a coherent summary. Abstractive summarisation, in comparison, is not limited to words present in the text; rather, it involves drawing upon a large dictionary of candidate words. Extractive summarisation has the advantage of utilising present words, making it easier to generate a coherent summary, but this also places constraints on its potential expressivity. Abstractive summarisation, on the other hand, has greater expressive potential but is a more challenging task.

Previous work has looked at finding a compromise between the two methods.23 used a pointer-generator network to provide an extractive fall-back during abstractive summarisation.24 performed abstractive summarisation with the dictionary restricted to words included within main text. While viable titles were generated, the original headlines still scored higher on human evaluation.

The challenges of summarising the spoken word

The spoken word differs from the written word in important ways. Additionally, there is a paucity of human-annotated data for spoken word and pre-trained language models learn predominantly from the written word.

Furthermore, visual information and non-spoken audio are often needed to gain insight into the context of a video and it may in some cases be impossible to predict a video’s title without these. In addition, characteristics of speech such as tone of voice, speech tempo and intonation, which also help to convey the style of the video, are usually lost when condensing into textual form.

Likely as a reflection of these challenges, we are only aware of one study that has looked at this problem.4 fine-tuned BERTSUM on a combination of news article summaries (the CNN/DailyMail dataset25), documents summaries (the Wikihow dataset26) and human-generated summaries for auto-generated transcripts from the How2 Dataset274. They found their model could output summaries comparable to the human-generated ones on the How2 Dataset.

Methodology

The Data

We present the YouTube Titles and Transcripts (YTT) dataset, which consists of 17,886 YouTube video titles and accompanying human-generated video transcripts. We also include an expanded, unfiltered version consisting of 1.16 million titles and transcripts. Both are made publicly available: https://github.com/chris-lovejoy/youtube-titles-and-transcripts. We additionally used the How2 Dataset, which comprises 80,000 short instructional YouTube videos with English transcripts, for external validation of our final model.

The YouTube Titles and Transcripts Dataset

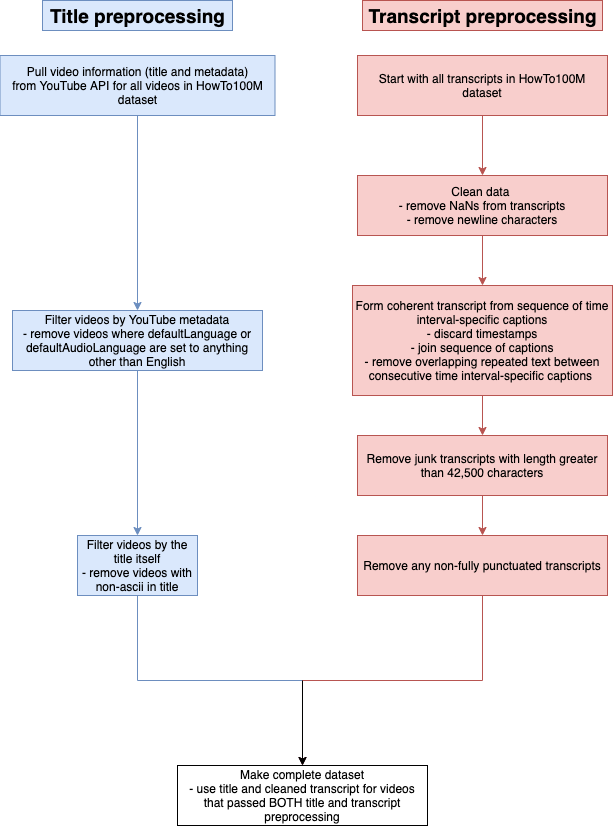

To create the dataset, we collated video clip captions from the HowTo100M dataset28 and paired them with video titles retrieved from the YouTube API. The HowTo100M dataset consists of 136 million video clips from 1.2 million YouTube videos. We collated video clips by concatenating captions and removing timestamps to create a single complete transcript per video. For the ‘clean’ version of the dataset, we removed videos which did not meet the following criteria: (i) titles only contain ASCII characters, (ii) transcripts are human-generated and fully punctuated and (iii) language confirmed as English in the YouTube metadata. The resultant dataset consists of 17,886 video transcripts and titles. For this study, we divided these videos into a random 80/20 train/test split, using the same split for all of our models to ensure fair comparison. The full processing pipeline is described in appendix.

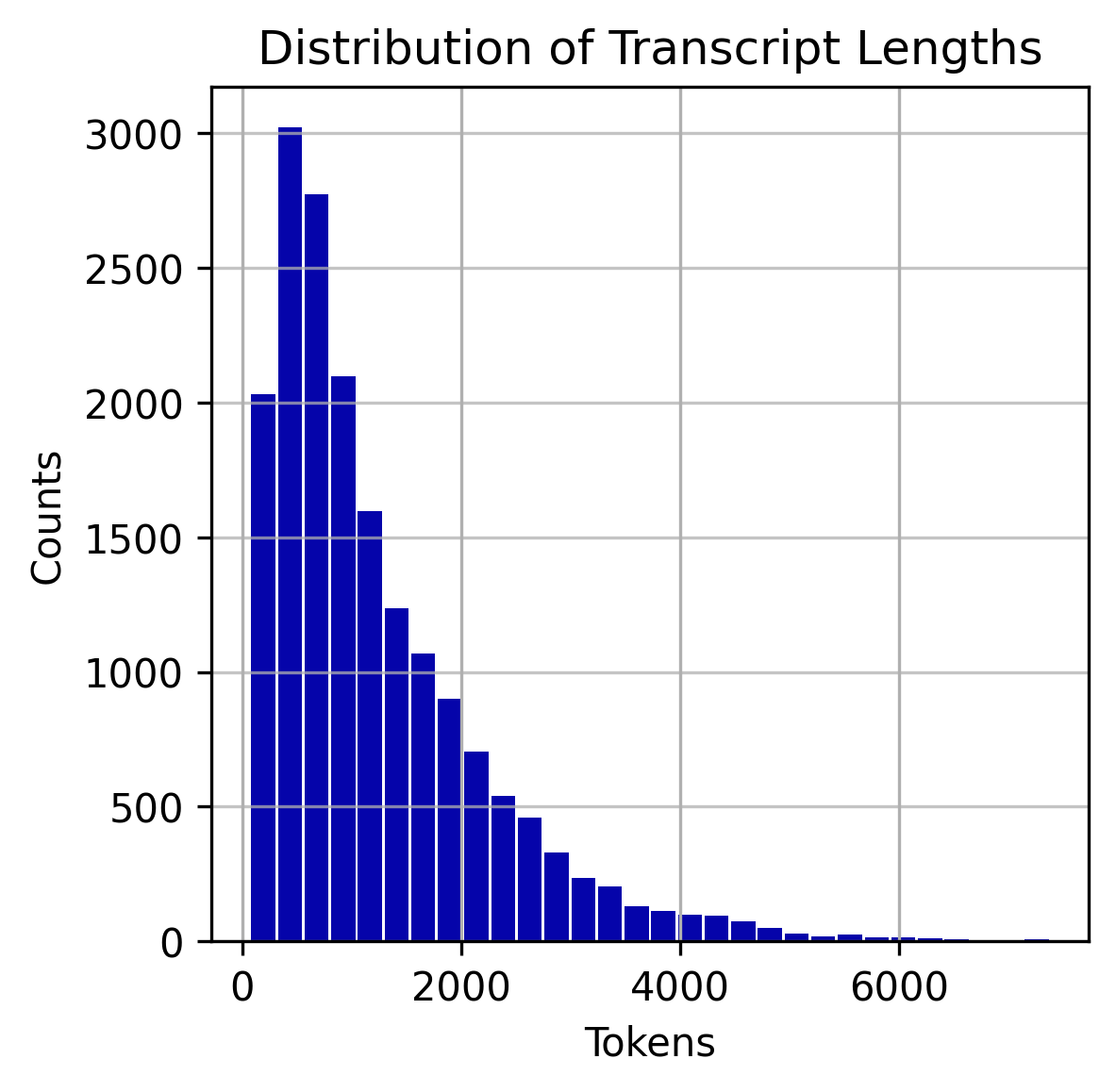

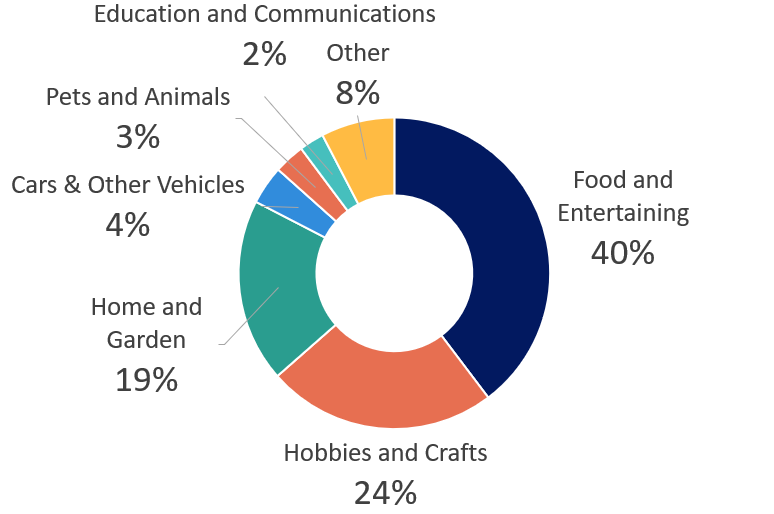

The dataset includes supplementary information from the HowTo100M dataset, including video category (e.g. “Food and Entertaining” or “Health”), sub-category (e.g. “Recipes” or “Conditions and Treatments”) and the search term originally used to find the video (e.g. “How to Paint a Motorcycle”). The average transcript length is 6,503 characters or 1,232 words, with a distribution shown in figure 1. The main categories (“Category 1” in the YouTube HowTo100M dataset) are shown in figure 2.

The original intention of the HowTo100M dataset was to create a text-to-video retrieval search engine for “how-to” videos, with “an emphasis on instructional videos where content creators teach complex tasks with an explicit intention of explaining the visual content on screen”. This introduces a bias in the types of videos present in the dataset. Additionally, it only contains videos less than 2,000 seconds long, with more than 100 views and containing more than 100 words. Full details of this dataset can be found in the original paper28.

Fig 1: Distribution of transcript lengths in dataset

Fig 1: Distribution of transcript lengths in dataset

Fig 2: Split of video categories in dataset

Fig 2: Split of video categories in dataset

The How2 Dataset

The How2 Dataset contains human-generated, punctuated transcripts for approximately 80,000 instructional videos27. The average video length is 90 seconds long and 291 words in transcript length. Around 21,000 of these videos are still available on YouTube. We extracted the titles from the YouTube API and used these videos as an external test set for our model.

The Models

LSTM: A long short-term memory network (LSTM) was implemented as an encoder-decoder model with an attention mechanism29. Attention allows modelling of dependencies independently of their distance in input or output sequences30. The specific model architecture used is described in31.

LSTMs have been praised for remembering dependencies as long as 1,000 timesteps32. However, the mean transcript length in our dataset is over 1,200 words and, combined with the diversity and complexity of transcripts, may still present a challenge.

PEGASUS: PEGASUS is a novel pre-trained transformer-based encoder-decoder model, developed for the purpose of summarisation5. It utilises a novel pre-training objective of ‘gap sentences generation’ (GSG), whereby whole sentences within documents are masked and the model is trained to reproduce them.

PEGASUS achieves human performance on a variety of summarisation datasets and has shown strong downstream performance with finetuning on as few as 1,000 training examples5. We hypothesised that such a model would be a strong candidate to finetune for the task of generating video titles, which may be viewed as one-sentence length summaries of video transcripts.

GPT-2: While PEGASUS is designed specifically for text summarisation, we hypothesised that an alternative approach could plausibly perform better: treating video title generation as a forward-predictive task. GPT-233 is a transformer-based language model, pre-trained on OpenAI’s WebText dataset33, which has achieved SOTA results in a range of text generation domains6. It was therefore selected as the best model to test our hypothesis, by tasking it to predict the title of a video having seen the transcript.

Additional Preprocessing Methods

GPT-2 and PEGASUS have maximum sequence lengths of 1,024 and 512 tokens respectively. GPT-2 considers the last 1,024 tokens as a sliding window while generating the title. For PEGASUS, only the first 512 tokens of the transcript are taken into account when generating an abstractive summary. As many video transcripts are longer than these maximum sequence lengths, large parts of the transcripts will be completely ignored when titles are generated. Methods for preprocessing the raw transcripts to provide the best input to the models were therefore explored.

Extractive Summarisation

A modified BERT model was used to generate extractive summaries of the full video transcripts that could be used as inputs. Specifically, the extractive summarisation technique outlined by34 was used. This involves generating text embeddings using a pretrained BERT model then using K-means clustering to select the embedded sentences that are closest to the centroid. By selecting the number of centroids, it is possible to determine the number of sentences to include in the summary. We hypothesised that this would enable the models to consider more information, and therefore generate more accurate titles.

We aimed to generate transcript summaries as close to the maximum token length that PEGASUS or GPT-2 can handle. However, in many cases BERT struggled to find appropriate summary sentences for this length and returned shorter summaries. Summaries shorter than 30 tokens in length were excluded from further training and testing. For GPT-2, when the extractive summaries were shorter than the input capacity, the remaining capacity was filled with the end of the original transcript. A special token was used to indicate where the raw transcript segment ends and the extractive summary begins.

One limitation we note is that the objective for BERT is to make the best summary, not necessarily to create the best inputs for a video title generation model.

Preprocessing Using Transcript Reordering

An alternative preprocessing method explored for GPT-2 was to feed in the final 522 tokens of the transcript, followed by a special token to indicate a boundary, then the first 500 tokens of the transcript. The model therefore sees the ‘tail’ segment of the transcript followed by the start of the transcript, before then generating its title. We hypothesised that the most useful information about the subject of the video would typically be contained near the beginning and end of the transcripts, where the subject matter is likely to be introduced and concluded respectively.

Experiments

Our overall experimental pipeline was the following: Firstly, we trained and tested the LSTM, PEGASUS and GPT-2 on full video transcripts from the YTT dataset. Following this, BERT was used to extractively summarise the transcripts and both PEGASUS and GPT-2 were trained and tested using these summaries. Finally, different methods of training and using GPT-2 were explored and an optimal model identified. Model outputs were generated for the YTT and How2 datasets, with the former being additionally assessed by human evaluation.

Datasets

After fine-tuning our model on the YTT dataset, we evaluated it on the test portion of the YTT dataset and on the How2 dataset. The characteristics of these datasets are described in methodology section.

Model Training

LSTM: An LSTM was trained in the first experiment to establish a baseline performance. It was trained for 14,000 stochastic gradient descent (SGD) steps, with a learning rate of 0.01 and a dropout probability of 0.135. Teacher forcing was used with probability 0.5. When generating titles, the word with the highest probability according to the softmax layer of the decoder was selected at each timestep.

GPT-2: For each method, GPT-2 was fine-tuned for 5 epochs. The beginning and end of each training item were designated by the special tokens <|startoftext|> and <|endoftext|>. For the extractive summarisation method we used a special token <|summary|>, to designate the end of the raw transcript and the beginning of the summary produced by BERTSUM. Similarly, when reordering the transcript we used a special token <|beginning|> to designate the end of the raw transcript with the first 500 tokens cut out, and the start of the section containing those 500 tokens. For all methods we used a special token <|title|>, to designate the end of the input and the beginning of the title. Titles were generated using BEAM search with a beam width of 5, a maximum title length of 20 tokens, and the model was prevented from generating repeating sequences of length 3 tokens or longer to avoid producing unrealistic repetitive titles.

PEGASUS: We used the “Mixed and Stochastic” PEGASUS model5, pre-trained on 1.5 million examples from the C4 and HugeNews datasets with a gap sentence ratio between 15% and 45% (the gap sentence ratio is the proportion of sentences used for the sentence generation training objective). For each version, PEGASUS was fine-tuned for 3 epochs on a Tesla P100 GPU. The learning rate followed an initial 500-step warmup period, during which it increases from 0 to 0.01, followed by an AdamW optimiser with weight decay of 0.01, β1 of 0.9 and β2 of 0.999 to determine the remainder of the learning rate schedule.

Evaluation

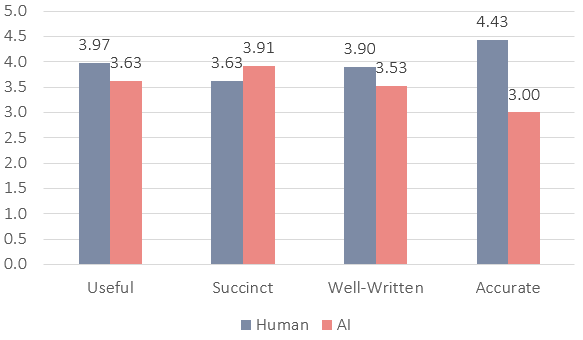

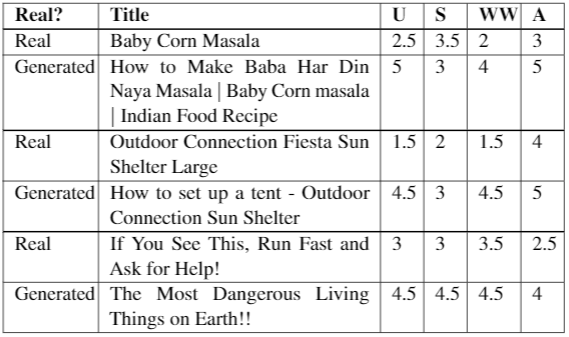

To assess the performance of our models we used the standard abstractive summarisation ROUGE-1, ROUGE-2 and ROUGE-L metrics36 and additionally performed human evaluation on our best performing model. The human evaluation was undertaken by 25 evaluators (all of whom are friends or relatives of the authors). Each was provided with the AI and human-generated titles for 24 videos from the YTT dataset and asked to rate each title from 1-5 on how (i) useful, (ii) succinct and (iii) well-written it is as well as to predict which title was created by the AI. The full criteria were a modified version of that used by24 (details in appendix). By having two human evaluators for most of the videos, around 300 unique videos were appraised in this manner. Additionally, each evaluator was given links to ten different YouTube videos from the YTT dataset and asked to rate the true and generated titles based on how accurately the title reflected the video content (again, from 1-5). While the first tasks were designed to measure the model’s ability to create coherent titles, the latter task assesses whether the generated titles truly capture the essence of each video.

Results and Discussion

| Model | Rouge-1 | Rouge-2 | Rouge-L |

|---|---|---|---|

| LSTM | 0.103 | 0.023 | 0.099 |

| Vanilla PEGASUS | 0.160 | 0.065 | 0.143 |

| PEGASUS with extractive summarisation | 0.128 | 0.048 | 0.117 |

| Vanilla GPT-2 | 0.242 | 0.112 | 0.230 |

| GPT-2 with extractive summarisation | 0.248 | 0.114 | 0.233 |

| GPT-2 with transcript reordering | 0.265 | 0.123 | 0.249 |

Table 1: ROUGE scores for our six model variants. The ROUGE scores displayed are the mean ROUGE F1 scores on the test dataset.

The LSTM performs poorly by predicting generic titles

The LSTM has the lowest ROUGE scores on all three measures (Table 1) and qualitative inspection of generated titles also shows poor performance.

For the vast majority of titles, the LSTM just predicts a generic title that suits the genre rather than the specific video. Example titles include “How To Make A - The -“, “Homemade Recipe ( Recipe with )” and “DIY To Recipe - DIY - DIY - DIY Tutorial”. The broad theme is often picked up on, but the titles themselves have low utility.

A likely factor is the length of transcripts, which averages more than 1,200 words. The recursive nature of LSTMs means that it is difficult to capture long-term dependencies even with attention37. The length of the paths forward and backward signals have to traverse scales linearly with the sequence length38. Another contributing factor may be that the LSTM struggles to learn rich word embeddings from so few training examples (14,000 in total). There are likely to be words in the test set transcripts that do not appear, or appear rarely, in the training set transcripts.

GPT-2 creates more title-like titles, while PEGASUS creates full sentences

PEGASUS-generated titles improve on the LSTM both in ROUGE score (Table 1) and on qualitative inspection but are inferior to those generated by GPT-2 on both counts. The PEGASUS-generated titles often appear useful, however they tend to be long, taking a full sentence format, which negatively impacts the ROUGE scores. For example, for the video “How to Make Chicken Nanbanzuke (Recipe) - Cooking with Dog”, the PEGASUS-generated title was “In this week’s episode of ‘Cooking with Dog’, Francis shows us how to prepare Nanban vinegar sauce and chicken thigh with potato starch.”. This is an accurate description of the video contents but the ROUGE score is low due to its length. In comparison, the LSTM-generated title “Baked Recipe ( Recipe with )” obtains a higher ROUGE score.

GPT-2-generated titles are often shorter than the true titles and have a more ‘title-like’ form than those generated by PEGASUS. For example, for the video “Corned Beef Hash - Easy One Pot Recipe - Cait Straight Up”, GPT-2 generates the title “Corned Beef Hash Recipe”. This lends support to Video Title Generation being more appropriately viewed as a forward-prediction task rather than a summarisation task. (Further examples of generated titles are available in appendix).

There are several likely reasons why these pre-trained language models outperform the LSTM. The self-attention mechanism used by transformer models makes it easier to learn long-range dependencies39. While the LSTM may struggle to learn rich word embeddings from a dataset of our size, pre-trained language models have already learnt universal language representations40. Pre-trained models can provide better model initialization, which usually leads to better generalization performance and speeds up convergence on downstream tasks40.

GPT-2 may outperform PEGASUS because it has been pre-trained on a more task-agnostic objective: predict the next word given all the preceeding words. PEGASUS is trained to predict entire sentences for summarisation. So, even after fine-tuning on our downstream task, it is still likely to predict a title that is both a grammatical sentence and a summary. Thus, viewing video titles as sentence-length summaries of the video may in fact not be appropriate.

Raw transcripts as inputs yield better results than BERT summaries

Given the length of the video transcripts (often far exceeding the input limit for our models), identifying the most salient parts is an important challenge of Video Title Generation. For shorter transcripts, where less selection of the transcript is required, our models performed better (see results for final model in Table 4).

The pipeline outlined in this section (of feeding extractively-summarised transcripts into our models) did not notably improve model performance, contrary to our hypothesis.

For our PEGASUS model, the average ROUGE scores were worse when using the extractively-summarised transcripts than the full transcripts (see Table 1). Upon inspection, it appears that the model often hones in on specific elements of the video, losing sight of the bigger picture. For example, for the video “Belgian Waffles taste test in Bruges, Belgium”, the original PEGASUS produced “In our series of letters from African journalists, filmmaker and columnist Farai Sevenzo looks at one of Belgium’s most famous foods.” while PEGASUS with extractive summarisation generated “We are in Brussels!”. It focused on the country, but not the essence of the video (about Belgian waffles).

For the GPT-2 model, the average ROUGE scores are much the same (see Table 1). However, on inspection there appear to be some similar errors; where the bigger picture is lost for a specific detail. For example, the video “OUR BALL PIT FLOODED! Crazy Washer Machine + Chick-Fil-A No Like Shawn (FUNnel Vision Flood Vlog)’’ features a broken washing machine. The original GPT-2 model produces “How to fix a leaky washing machine’’ (showing a bias towards ‘how to’-type titles, but still retaining the overall theme) while the GPT-2 model with extractive summarisation generates “The Worst Day Ever” (which relates to complaints from those in the video about the impact of the broken washing machine).

It may be that important information from the transcripts is lost when it is extractively summarised by BERT. This may represent the BERT model having been trained to make the best summary, not necessarily the best inputs for a Video Title Generation model. Alternatively, BERT may have struggled to find the most relevant sentences in our dataset because it was pre-trained on written text rather than spoken word. Future work could explore extractive summarisation techniques that are more tailored to the task at hand.

A central challenge of Video Title Generation is generalisability

There is a huge diversity in both the nature of video content and the styles of video titles in our dataset, and on YouTube as a whole. This makes Video Title Generation, as we have defined it, an inherently challenging task.

Despite its diversity, one limitation of our YTT dataset is that it only represents a tiny subset of all the different types of video that exist on the internet. For example, all of the videos included were initially retrieved using searches for “how-to” videos and are less than 2,000 seconds long. They are thus not necessarily representative of all available videos.

Within our subset of videos, there are notably more videos in certain categories (as shown in Figure 2). Out of 19 categories, more than 75% of videos fell into one of three: Food and Entertaining (40%), Hobbies and Crafts (24%) and Home and Garden (19%). The average performance of our model on these categories appears higher than on less-represented categories, as shown in Table 2. This suggests that performance for under-represented categories may feasibly improve as dataset size is expanded.

| Average scores | Categories with >500 videos | Categories with 50-500 videos |

|---|---|---|

| ROUGE-1 | 0.270 | 0.237 |

| ROUGE-2 | 0.126 | 0.109 |

| ROUGE-L | 0.255 | 0.225 |

Table 2: Average ROUGE scores across videos in common vs uncommon categories in the YTT dataset

| Average scores | YTT dataset | How2 dataset |

|---|---|---|

| ROUGE-1 | 0.265 | 0.270 |

| ROUGE-2 | 0.123 | 0.133 |

| ROUGE-L | 0.249 | 0.259 |

Table 3: Performance of the best-performing GPT-2 model on the YTT and How2 datasets

| Average scores | <1000 tokens (n = 1604) | Between 1000 and 5000 tokens (n = 1832) | >5000 tokens (n = 104) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ROUGE-1 | 0.289 | 0.249 | 0.188 |

| ROUGE-2 | 0.142 | 0.110 | 0.057 |

| ROUGE-L | 0.272 | 0.234 | 0.173 |

Table 4: Performance of the best-performing GPT-2 model on transcripts of different lengths

Our final model obtained ROUGE scores on the How2 dataset that were comparable to those on the YTT dataset (see Table 3). This provides some evidence of model generalisability. However, as the How2 dataset also has a focus on how-to instructional videos, further validation on other video types would be necessary to support this conclusion. On manual inspection, there is an evident bias towards generating titles that start with ‘how to’. We also noted that in some cases the model was picking up title structures that were used by the original content creator. For example, several titles in the training set ended with “- Cooking with Dog”. One such example in the test set was “How to Make Chicken Nanbanzuke (Recipe) - Cooking with Dog”, for which the model predicted “How to Make Nanban Vinegar Sauce - Cooking with Dog”. This suggests the model may be memorising aspects of the training data and in some cases such structural biases may be undesirable. Expanding the size and diversity of content may help reduce the risk of this.

GPT-generated titles are often more succinct and informative than original titles, but suffer from inconsistency and low accuracy

The best-performing model was GPT-2 utilising the transcript re-ordering preprocessing method described in this section. This supports our initial hypothesis that the most useful information is near the beginning and end of transcripts.

Human evaluation identified generated titles as more succinct than the true titles but lower on how useful, well-written and accurate they were on average (Figure 4). Many individual AI-generated titles scored more highly than the human-generated alternatives and nearly 30% of AI-generated titles were confused for real titles by the evaluators. However, inconsistency in the quality of the model’s output pulls down the average score.

There is some evidence that the model is less prone to make “clickbaity” titles. For example, for a video titled “Why AI will probably kill us all”, the model generated “How AI will change your life”. Upon inspection, the generated title is a more accurate description of the videos contents. The apparent tendency away from “clickbait-iness” may reflect the nature of text used for pre-training. GPT-2 was pre-trained on high quality Reddit posts, where the incentive to ‘write for clicks’ has less direct incentive than the titling of YouTube videos. In many cases, the model produces more succinct titles that still include the core information. For the video “Top Ten Best OREO Recipes in 10 minutes - How To Cook That Ann Reardon”, for example, GPT-2 generated “How To Cook That: Oreos”. Many of the highly-rated generated titles begin “how to”, including when the true title does not. Further examples are available in appendix.

There are cases where the model has the right general theme, but misses the true focus of the video. For example, for the video “Primitive Technology: Cord drill and Pump drill”, the model generates “How to Drill a Hole in a Stone”. Here, the model may detect that much of the video content describes the mechanics of using the technology, even if that is not the primary focus. Sometimes more basic errors are seen, such as repetition: “Granny Granny Car and Granny Inside of the Granny Garage”. Repeating sequences have been previously noted as a common failure mode for GPT-241. We partially address this by enforcing no repeating sequences of 3 tokens or more, but this still permits titles like the example above above. A further step could look to selectively allow repetition of more common tokens such as “the” but not less common tokens such as “Granny”.

Conclusion

In this paper, we have outlined Video Title Generation as a novel training objective for video summarisation and shared the first publicly-available dataset of titles and associated transcripts.

We have demonstrated that this task is best formulated as a forward-predictive task and that GPT-2, using the start and end of transcripts, can achieve performance that approaches or exceeds human-level performance in certain domains. Most notably, generated titles were more succinct.

Of our original hypothesis, we saw some evidence that generating human-level video titles from transcripts is possible (Hypothesis 1) and that these titles are less “clickbait-y” (Hypothesis 2). We found that GPT-2 is superior to PEGASUS (Hypothesis 3) and that transcript re-ordering works better than extractive summarisation (Hypotheses 4 and 5).

We envisage many potential applications of this work, from use in video search engines to content moderation to supporting users’ videos consumption decisions.

One avenue of future improvements is technical; we see multi-task learning for the simultaneous prediction of video category as one logical progression. Replicating our study in alternative video types (beyond the focus on instructional videos) would support and extend our findings.

Our work could also be extended to generate longer summaries, perhaps as bullet-points, which may have higher utility than titles alone. Additionally, multimodal approaches could be considered27 to incorporate the visual information that videos contain. Such work would be necessary to extend our approach to videos where speech is not the principal modality.

Appendix

Cleaning the data

Titles

In order to remove non-English videos, we filtered out all videos with YouTube attributes defaultLanguage and defaultAudioLanguage set to anything other than English. In addition, we only included videos with titles containing only ASCII characters. After an inspection of the dataset, these criteria appeared to be effective in removing obscure or foreign videos or videos otherwise not suitable for the task at hand.

Transcripts

In addition to the challenges already discussed in handling the spoken word in the context of natural language processing, another difficulty encountered with this task is that of acquiring transcripts that accurately capture the speech contained within a video, both in terms of reporting each intended spoken word correctly and providing punctuation in the appropriate places to ensure fluency and correct grammar. YouTube does provide auto-generated captions for many uncaptioned videos. However, these are not entirely suitable to feed into a pretrained language model as they are segmented captions rather than complete transcripts. Hence, they contain very little punctuation and are also susceptible to inaccuracies such as misreporting words for similar sounding yet inappropriate words. Therefore we focus the majority of our analysis on fully punctuated transcripts which we found in general to be much more accurate as they are manually annotated.

Adapting the captions from the HowTo100M dataset into full coherent transcripts posed a number of challenges. Firstly, we removed numerous NaNs found in some transcripts and performed other basic data cleaning tasks such as removing newline characters. Secondly, because the dataset was created for a video clip search engine, the text from the videos are arranged in the form of separate captions, with many captions per video, and linked with timestamps to denote when that captions appears in the video. We discarded these timestamps as they are not relevant for this task. In some cases, simply concatenating the captions into one large string per video was sufficient to form a complete transcript. However, sometimes we encountered text which overlapped from one caption to the next. Therefore we removed any overlaps to ensure coherency. In addition, we removed any transcripts more than 42,500 characters long as these were more often than not junk transcripts which did not reflect the spoken content of the video.

Finally, in order to filter out auto-generated/poor quality transcripts we removed any transcripts which were not fully punctuated. In practice, we found the most accurate indicator of a fully punctuated transcript was if it contained at least one comma followed by a space and at least one full stop followed by a space.

Fig 4: YouTube Titles and Transcripts data preprocessing

Fig 4: YouTube Titles and Transcripts data preprocessing

Human evaluation criteria

Criteria

What makes a good video title? It should be…

- Useful. Does it have enough information to make a user decide whether they want to spend time watching the video? Is it obvious from the title what the video is about?

- Succinct. It should not be too long or full of extra details.

- Well-written. There should not be grammatical errors, awkward wording or confusing or contradicting statements in the title.

LSTM titles vs PEGASUS titles

Table 5 compares LSTM generated titles and PEGASUS generated titles.

| True title | LSTM Predicted title | LSTM Case sensitive ROUGE | LSTM Case insensitive ROUGE | PEGASUS Predicted title | PEGASUS Case sensitive ROUGE | PEGASUS Case insensitive ROUGE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irish People Try American Sandwiches | DIY - How To Make A - | 0.00 | 0.00 | In honour of National Sandwich Day, BBC News food correspondent Clarissa Sebag-Montefiore takes a bite of some of America’s best-loved sandwiches. | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Basic Cocktails - How To Make The Paper Plane | The the - - | 0.14 | 0.14 | The paper plane is a modern classic cocktail developed by Sam Ross and the late Sasha Petroski of milk and honey fame | 0.04 | 0.18 |

| How To Keep Brown Sugar Soft | How To Make A | 0.35 | 0.35 | How to store brown sugar indefinitely without it getting hard | 0.08 | 0.43 |

| How to Make Chicken Nanbanzuke ( Recipe ) | Cooking with Dog | Baked Recipe ( Recipe with ) | 0.30 | 0.30 | In this week’s episode of “Cooking with Dog”, Francis shows us how to prepare Nanban vinegar sauce and chicken thigh with potato starch. | 0.08 | 0.18 |

| How To Make Energy Bars - GCN ‘s Food For Cycling | How To Make - - - - | 0.38 | 0.38 | In the second part of our series on making your own energy bars, GCN’s nutrition expert, Simon, shares his secret recipe. | 0.04 | 0.09 |

Table 5: Comparison between some LSTM generated titles and PEGASUS generated titles. The ROUGE F1-scores shown are the means of the ROUGE-1, ROUGE-2, ROUGE-L F1-scores for each title (both case sensitive and case insensitive). One can see that the LSTM titles, being short, may obtain comparable or superior ROUGE scores to the PEGASUS titles. This is despite the PEGASUS titles, which receive low scores due to their long length, being better titles

LSTM titles vs PEGASUS titles vs GPT-2 titles

Table 6 displays example titles produced by the LSTM, PEGASUS and GPT-2 models.

| True title | LSTM | PEGASUS | GPT-2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grilled Lamb Chop Recipe - Super Easy, Healthy, Quick And Yummy For Dinner Or Lunch | How To Make - - - - | All images are copyrighted. | How to Grill Lamb chops |

| How To Make Pom Poms 2 Ways! | DIY Stable & DIY Cookies | In this video tutorial, I’m going to show you how to make pom poms out of cardboard. | How to Make Pom Poms |

| THE BEST VEGAN BURGER | Recipe by Mary’s Test Kitchen | VEGAN VEGAN VEGAN VEGAN VEGAN #3 - The with | This is the juiciest vegan burger I’ve ever made. | How to make vegan burger |

| RAINDROP CAKE Recipe Mizu Shingen Mochi - You Made What?! | What Happens A - The in | In this week’s “You Made What?”, I’m going to show you how to make a cake using agar agar. | Raindrop Cake Recipe (Mochi) |

Table 6: Examples of titles produced by our models

| True title | Generated title | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Advanced 3 Club Juggling: Juggling 3 Clubs: 441 Siteswaps | How to juggle clubs | This generated title received a ROUGE score of 0 and is another example of the shortcomings of the ROUGE metric |

| How to Train a Parrot: How to Potty Train a Parrot | Potty Training Your Parrot | - |

| What to Wear for First Dates: Accessories to Avoid on Bowling Dates | How to Dress for a Date | Some generated titles are not “wrong” but miss details of the video |

| How to Iron a Suit: How to Iron Dress Pants | How to Sew a T-Shirt | Some generated titles capture the wrong meaning |

| How to Make a Cloth Grocery Bag: Finished Product for Cloth Grocery Bag | How to Sew a Stitch on a Handle |

Table 7: Some example titles generated by GPT-2 on the How2 dataset.

External validation on How2 dataset

Please see Table 7.

Examples where generated titles from final model are preferred to true titles

Citing this work

If you found this useful, please cite this write-up as:

Lovejoy, Davies, Till and Prosser. (Jun 2021). The Truth Is In The Title? Video Title Generation as a novel training objective for video summarisation. https://chrislovejoy.me/video-title-prediction

or

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

@article{lovejoy2021videotitle,

title = {The Truth Is In The Title? Video Title Generation as a novel training objective for video summarisation},

author = {Lovejoy, Davies, Till and Prosser},

journal = {chrislovejoy.me},

year = {2021},

month = {Jun},

url = {https://chrislovejoy.me/video-title-prediction}

}

References

Greg Jarboe. 2019. By 2021, 80% of the World’s Internet Traffic Will Be Video [Cisco Study] – Tubular Labs. ↩︎

James Hale. 2019. More Than 500 Hours Of Content Are Now Being Uploaded To YouTube Every Minute. ↩︎

Craig Smith. 2024. 160 Amazing YouTube Statistics and Facts - By the Numbers ↩︎

Alexandra Savelieva, Bryan Au-Yeung, and Vasanth Ramani. 2020. Abstractive Summarization of Spoken and Written Instructions with BERT. arXiv preprint arXiv:2008.09676. ↩︎ ↩︎2 ↩︎3 ↩︎4

Jingqing Zhang, Yao Zhao, Mohammad Saleh, and Peter J. Liu. 2019. PEGASUS: Pre-training with Extracted Gap-sentences for Abstractive Summarization. CoRR, abs/1912.08777. ↩︎ ↩︎2 ↩︎3 ↩︎4

Jieh-Sheng Lee and Jieh Hsiang. 2019. Patent Claim Generation by Fine-Tuning OpenAI GPT-2. CoRR, abs/1907.02052. ↩︎ ↩︎2

Soheyla Amirian, K. Rasheed, T. Taha, and H. Arabnia. 2021. Automatic Generation of Descriptive Titles for Video Clips Using Deep Learning. ArXiv. ↩︎

H. P. Luhn. 1958. The automatic creation of literature abstracts. IBM Journal of Research and Development. ↩︎

Rada Mihalcea. 2005. Language independent extractive summarization. Proceedings of the ACL 2005 on Interactive poster and demonstration sessions. ↩︎

Michele Banko, Vibhu O. Mittal, and Michael J. Witbrock. 2000. Headline Generation Based on Statistical Translation. ↩︎ ↩︎2

Konstantin Lopyrev. 2015. Generating News Headlines with Recurrent Neural Networks. ↩︎

Ayana, Shiqi Shen, Yu Zhao, Zhiyuan Liu, and Maosong Sun. 2016. Neural Headline Generation with Sentence-wise Optimization. arXiv:1604.01904. ↩︎

Shun Kiyono, Sho Takase, Jun Suzuki, Naoaki Okazaki, Kentaro Inui, and Masaaki Nagata. 2017. Source-side Prediction for Neural Headline Generation. arXiv:1712.08302. ↩︎

Peng Xu and Pascale Fung. 2019. A novel repetition normalized adversarial reward for headline generation. arXiv:1902.07110. ↩︎

Bonnie Dorr, David Zajic, and Richard Schwartz. 2003. Hedge Trimmer: A Parse-and-Trim Approach to Headline Generation. ↩︎

Katja Filippova and Y. Altun. 2013. Overcoming the Lack of Parallel Data in Sentence Compression. ↩︎

Katja Filippova, Enrique Alfonseca, Carlos A. Colmenares, Lukasz Kaiser, and Oriol Vinyals. 2015. Sentence Compression by Deletion with LSTMs. ↩︎

David Zajic, Bonnie Dorr, and Richard Schwartz Bbn. 2002. Automatic Headline Generation for Newspaper Stories. ↩︎

Yuko Hayashi and Hidekazu Yanagimoto. 2018. Headline Generation with Recurrent Neural Network. ↩︎

Alexander M. Rush, Sumit Chopra, and Jason Weston. 2015. A Neural Attention Model for Abstractive Sentence Summarization. arXiv:1509.00685. ↩︎

Daniil Gavrilov, Pavel Kalaidin, and Valentin Malykh. 2019. Self-attentive Model for Headline Generation. In Advances in Information Retrieval, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pages 87–93, Cham. Springer International Publishing. ↩︎

Ruqing Zhang, Jiafeng Guo, Yixing Fan, Yanyan Lan, Jun Xu, Huanhuan Cao, and Xueqi Cheng. 2018. Question Headline Generation for News Articles. ↩︎

Abigail See, Peter J. Liu, and Christopher D. Manning. 2017. Get To The Point: Summarization with Pointer-Generator Networks. arXiv:1704.04368. ↩︎

Oleg Vasilyev, Tom Grek, and John Bohannon. 2019. Headline generation: Learning from decomposable document titles. arXiv preprint arXiv:1904.08455. ↩︎ ↩︎2

Ramesh Nallapati, Bowen Zhou, Cicero Nogueira dos Santos, Caglar Gulcehre, and Bing Xiang. 2016. Abstractive Text Summarization Using Sequence-to-Sequence RNNs and Beyond. arXiv:1602.06023. ↩︎

Mahnaz Koupaee and William Yang Wang. 2018. WikiHow: A Large Scale Text Summarization Dataset. arXiv:1810.09305. ↩︎

Ramon Sanabria, Ozan Caglayan, Shruti Palaskar, Desmond Elliott, Loïc Barrault, Lucia Specia, and Florian Metze. 2018. How2: a large-scale dataset for multimodal language understanding. arXiv:1811.00347. ↩︎ ↩︎2 ↩︎3

Antoine Miech, Dimitri Zhukov, Jean-Baptiste Alayrac, Makarand Tapaswi, Ivan Laptev, and Josef Sivic. 2019. Howto100m: Learning a text-video embedding by watching hundred million narrated video clips. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision. ↩︎ ↩︎2

Dzmitry Bahdanau, Kyunghyun Cho, and Yoshua Bengio. 2014. Neural machine translation by jointly learning to align and translate. arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.0473. ↩︎

Yoon Kim, Carl Denton, Luong Hoang, and Alexander M. Rush. 2017. Structured Attention Networks. CoRR, abs/1702.00887. ↩︎

Sean Robertson. 2021. NLP FROM SCRATCH: TRANSLATION WITH A SEQUENCE TO SEQUENCE NETWORK AND ATTENTION. PyTorch. ↩︎

Sepp Hochreiter and Jürgen Schmidhuber. 1997. Long short-term memory. Neural computation. ↩︎

Alec Radford, Jeff Wu, Rewon Child, David Luan, Dario Amodei, and Ilya Sutskever. 2019. Language Models are Unsupervised Multitask Learners. ↩︎ ↩︎2

Derek Miller. 2019. Leveraging BERT for Extractive Text Summarization on Lectures. arXiv:1906.04165. ↩︎

Geoffrey E. Hinton, Nitish Srivastava, Alex Krizhevsky, Ilya Sutskever, and Ruslan Salakhutdinov. 2012. Improving neural networks by preventing co-adaptation of feature detectors. CoRR, abs/1207.0580. ↩︎

Chin-Yew Lin. 2004. Rouge: A package for automatic evaluation of summaries. Text summarization branches out. ↩︎

Jingyu Zhao, Feiqing Huang, Jia Lv, Yanjie Duan, Zhen Qin, Guodong Li, and Guangjian Tian. 2020. Do RNN and LSTM have Long Memory? arXiv:2006.03860. ↩︎

Ashish Vaswani, Noam Shazeer, Niki Parmar, Jakob Uszkoreit, Llion Jones, Aidan N. Gomez, Lukasz Kaiser, and Illia Polosukhin. 2017. Attention Is All You Need. CoRR, abs/1706.03762. ↩︎

Sepp Hochreiter, Yoshua Bengio, Paolo Frasconi, and Jürgen Schmidhuber. 2001. Gradient Flow in Recurrent Nets: the Difficulty of Learning Long-Term Dependencies. ↩︎

Xipeng Qiu, Tianxiang Sun, Yige Xu, Yunfan Shao, Ning Dai, and Xuanjing Huang. 2020. Pre-trained Models for Natural Language Processing: A Survey. CoRR, abs/2003.08271. ↩︎ ↩︎2

L. Fröhling and A. Zubiaga. 2021. Feature-based detection of automated language models: tackling GPT-2, GPT-3 and Grover. PeerJ Computer Science 7:e443. ↩︎

Comments powered by Disqus.