The Academic Knowledge Management (AKM) system that 10x'd my research productivity

How I published 15 academic papers in my free time, using Obsidian, Zotero and Overleaf

Download the Obsidian template here

The part-time academic

Last summer I was battling the demands of fatherhood and being straight-up broke — juggling two jobs and a Master’s degree at University College London. But I wrote a top 10 machine learning dissertation, finished it two weeks early — and made time to holiday and publish another paper.

Over the past 5 years, I’ve published an academic paper every 3 months. But I’ve never worked as an academic. It’s something I do on the side.

I have a busy life: I’m a medical doctor who retrained as a machine learning engineer, founded a funded healthtech startup and recently became a father.

I’ve hacked together an academic knowledge management (AKM) system to digest academic papers and produce my own work, which requires minimal overhead, no fixed time commitment and is fundamentally different to any other system I’ve come across. It’s a game changer - whether you’re an academic or not.

It lets me perpetually progress things ‘on the backburner’, and to hop in and out of academia based on my interests and other commitments.

Taking this approach has only become possible recently, thanks to new tools and technologies. I’ll tell you what they are and why they’re so powerful.

UPDATE: This won a prize in the “Obsidian October” competition 2022 - check out all entries here.

What’s an AKM?

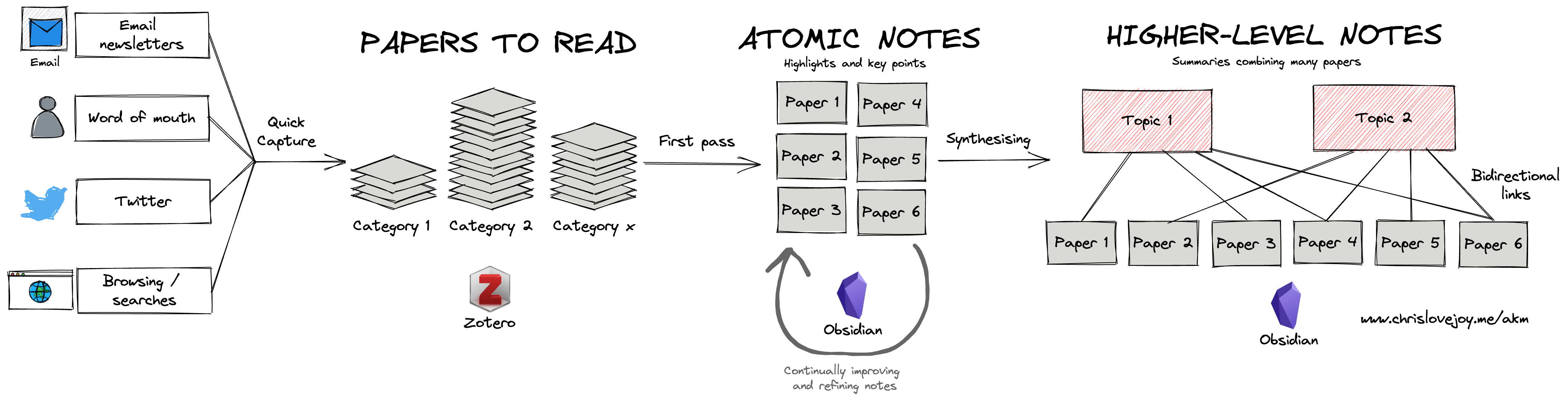

An AKM (academic knowledge management system) converts the slog of readings and writing papers into the following low-friction modular process:

- aggregating interesting papers to read

- extracting the key insights from each

- combining those insights into a bigger picture, easily-accessible reference for your future self (this is where the magic happens)

- exporting citations for a project

Modularising the process makes it easy to perform each step in isolation - even with big time delays between each step. For example, you might extract insights from a few interesting papers but then have a hectic 6-months and not look at them again. This system makes it easy to still come back and perform the next steps.

This is what my system looks like:

Let’s go through each step in turn.

Step 0: Create your academic home base

Having a single home base for all your papers and notes leads to some cool emergent properties:

- You can ‘carry forward’ knowledge from previous projects more easily.

- You can see links between subjects. Everything is related. Information doesn’t exist in discrete buckets. Having different topics stored in the same place enables these relations to become apparent more easily.

- You can iteratively improve your understanding over time, because you can revisit and previous notes within the same system.

This week, my AKM connected a literature review on time series forecasting I did a few years ago to a independent consulting project I’m doing on sleep stage prediction - giving me expert insight, immediately.

I use the following digital tools to enable this:

- Zotero for storing and indexing papers

- Obsidian for storing notes, highlights and higher-level synthesis.

- Overleaf for outputting written content, with references

I use Zotero because:

- It’s easy to use

- It’s open source

- It has the best Plug-Ins, providing a lot of versatility

(There are various alternatives though, like EndNote and Mendeley.)

Obsidian is phenomenal because it:

- enables a combination of folder-based and link-based note architecture. So notes on academic papers can be organised, but links between them can be easily made.

- make papers easily searchable and indexable

- is based on local files (no platform lock-in) and is written in plain text, which is future-proof (why write in plain text?).

(In theory, knowledgement management systems like Notion may work here but I think it’s much weaker on the above points.)

If you want to quickly set up your Obsidian folders, you can download my templates here.

Step 1: Quick capture of interesting papers

The time at which I become aware of a paper is typically not the best to read it. So I need a ‘quick capture’, save-it-for-later system which is low friction, regardless of the device.

The Zotero Connector is great for this, and works with any Chromium browser. I can save any paper into my library with one click. It automatically captures the metadata and will download the PDF if available.

I use the ‘Zotfile’ Zotero extension to automatically re-name PDFs into a consistent format and to save the PDFs into my Obsidian directory (which makes it easy to link notes I make to the PDF itself). If the PDF isn’t available, I can get it through institutional access and manually add.

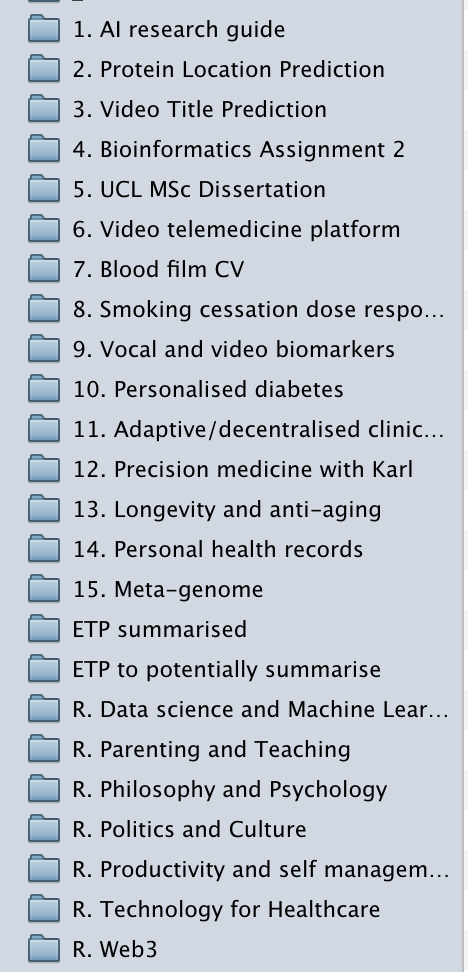

I’ve set up a folder structure within Zotero which encompasses the main areas that papers may fall into. I use a combination of Projects-based folders (organised as a numbered list) and broader areas of interest (starting with ‘R’ for ‘Resource’). This current looks like the following:

Note: The ‘Resources’ folders are aligned with folders that I have on my local computer (accessed through Obsidian), which maintains consistency with where the accompanying note will be created. The ‘Project’ and ‘Resource’ naming is a loose adaptation of Tiago Forte’s “PARA” structure.)

I become aware of interesting papers in multiple different contexts. It might be an email from Doctor Penguin or Research Rabbit, I might be doing a literature review or it might be a tweet.

At the point of capture, I make a quick decision around the appropriate folder: Is it part of a project? If not, which broad area of interest is it in? The one-folder-deep hierarchy makes this easy.

Then, when an appropriate situation arises, I can quickly see the new academic papers in my Zotero ‘inbox’, and pick off one to read. I make reading the papers low friction, too, by turning it into a modular task:

Step 2: Read and highlight the papers

I used to print out key papers and annotate the print out. It was a nightmare to store and access those printouts at a later date.

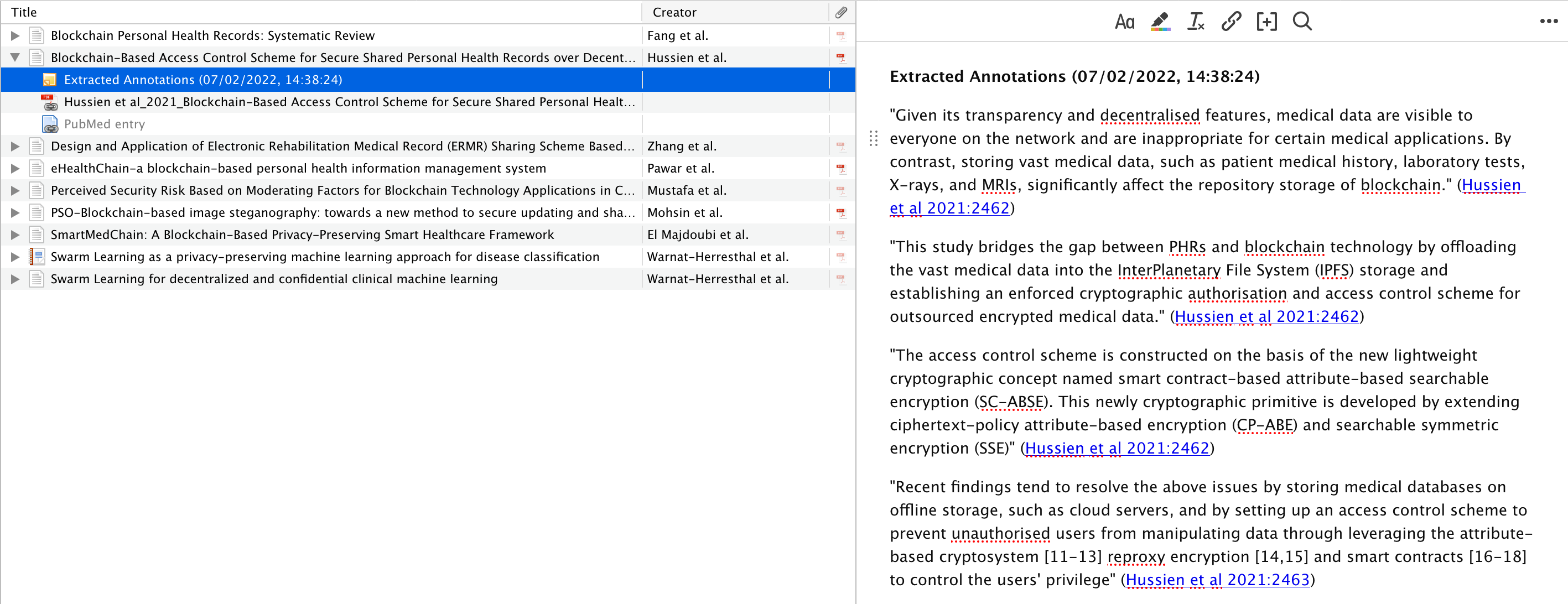

The workflow that has been a game changer for me is:

- Open the linked PDF through Zotero

- Read it, highlighting key sections and adding comments

- Export highlights and comments with the Mdnotes Zotero Plug-In

- Create an ‘atomic’ academic paper note in Obsidian with the title of the paper (Here’s an example). I’ll start with my paper template, using the ‘Templater’ plug-in and copy in my highlights and comments.

- Write a quick summary or key bulletpoints in my own words

It’s very easy to iteratively improve my notes, for example if I re-read the paper at a later date. The annotations have time-stamps, so I can re-extract the annotations and select the new ones.

Likewise, I can always add to and update my summary notes, using the principles of “Progressive Summarisation”.

The short summary of each paper is a great starting point for the next (and most important) step: synthesising findings from multiple papers.

Step 3: Get the bigger picture

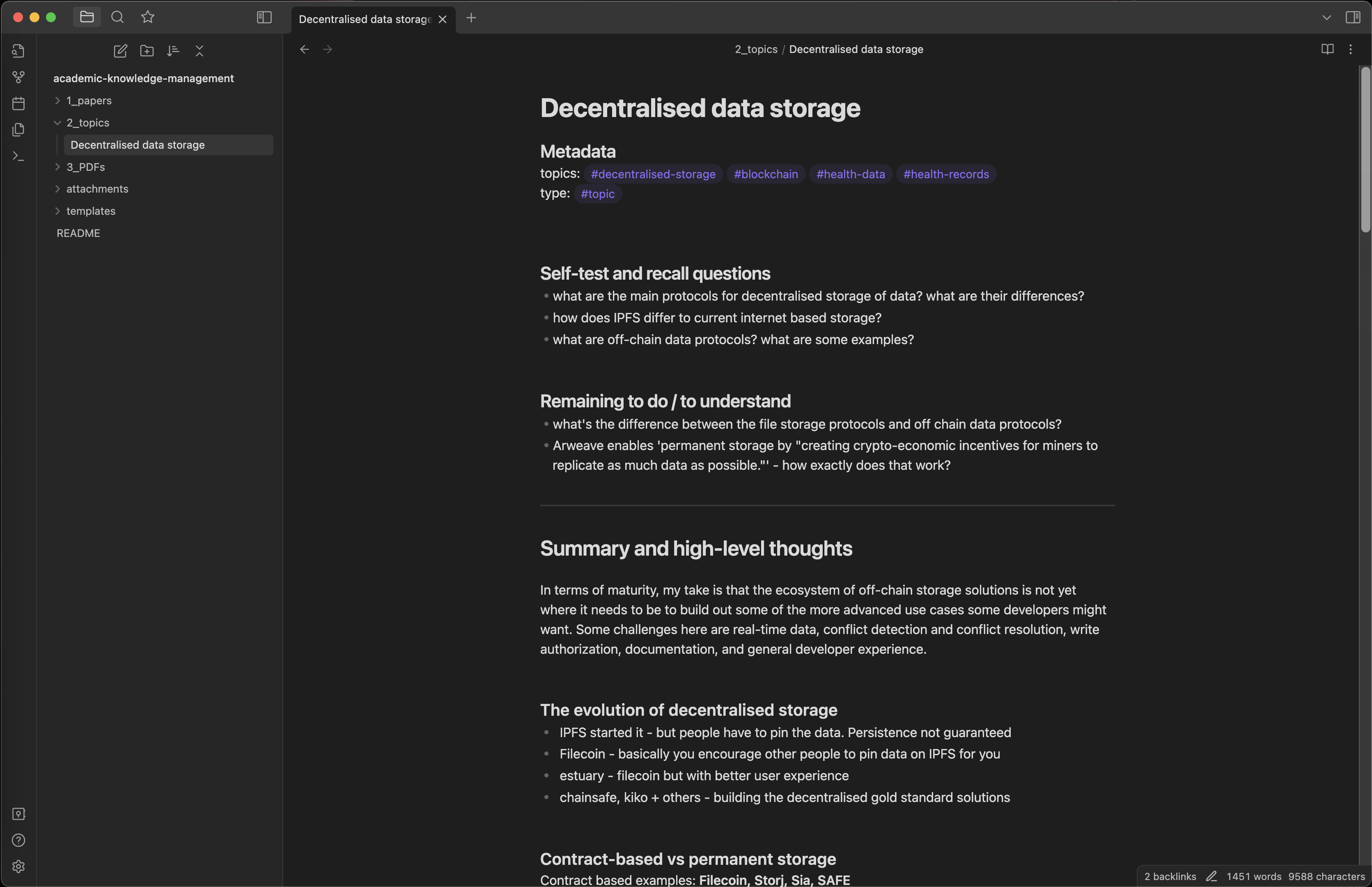

Individual papers themselves only provide a limited scope into a subject. To really understand an area, you need to integrate insights from multiple papers. For this, I create “topic” notes.

After reading several papers in an area, clear themes will begin to emerge. Once one does, I’ll create a note using my topic template, again using the ‘Templater’ plug-in. (Or if I’m doing a literature review for a project, I’d also create a topic note.)

The process is then as follows:

- Add links to all relevant papers in the ‘References’ section

- Copy across the summary from each paper into the topic note. (Given that I have atomic notes for each paper, it’s easy to open them all simultaneously and easily compare them side-by-side)

- Re-arrange the summaries and re-write in my own words to produce the best overview of my current state of understanding

I don’t follow a set structure for these topic notes. It emerges naturally based on the content.

However, I do have certain sections at the top of the note:

- A “Remaining To Do / To Understand” section, to highlight things I’m not sure about. This means I can move on without a “complete” understanding of the subject, and when I next visit the note I’ll know exactly where to start to improve it.

- A “Self-Test and Recall Questions” section, with prompts to encourage active recall of my understanding, particularly for when I haven’t reviewed the topic for a while.

Here’s an example of a topic note on decentralised data storage.

I’ll keep revisiting these topic notes and improve them over time (this example is still quite raw).

When I’m improving the topic note, I don’t limit myself to academic papers. I’ll incorporate other sources too, like blogs and book notes, which also go in the notes’ ‘references’ section.

This topic note becomes the entry point when I revisit a topic in future. This means I can get the key takeaways very quickly, but can also dive into references if needed. If I do look at the references, I’ll rarely read the full paper again as my highlights and summary notes are enough.

Sometimes, one paper will be relevant across multiple topics. This is where the beauty of the “networked notes” architecture comes in (which Obsidian enables). You can simply create a new topic note and add a reference to the same ‘atomic’ paper note.

Bonus: Effortlessly export the bibliography

This system makes it really easy to export the references if you write a paper.

If you’re exporting references into a word processor like Microsoft Word, you can just select the papers on Zotero and click ‘Create Bibliography from Items’.

Or if you’re using LaTex, you can export the references as a BibTeX file (the Better BibTex plug-in is really helpful here). If you use the citation keys in your write, It will automatically pick up the references, format them and produce a list of references at the end.

The impact of an AKM

Compounding benefits

I’m 18 months into having this system in full-flow and starting to see the benefits compound.

Last February, my startup was considering building a decentralised health data infrastructure. I read a bunch of academic papers, processing them using this system. In the end, we decided not to.

However, we pivoted in August and the decision became relevant again. My prior nuanced understanding had left my short-term memory, but I was able to easily hop back into the notes I’d made - and conclude that now it probably did make sense for us to.

Exploration

I’m finding I explore my interests much more. Before, I might have seen an interesting paper on, say, developmental psychology, but face some internal resistance around reading it. Because it wasn’t part of a project, I knew I’d likely forget it within a few months.

But now I’ll read it. I might only read one paper on a particular topic every 6 months, but the fact my AKM carries forward learnings means the knowledge still builds on itself.

Return on investment

When I was first setting this up, I had some doubt about whether it was a good time investment. Changing how you do something inevitably takes some time and effort.

But what helped is: the core elements of this setup is easy. It can be done within an hour or two, even if it sounds complex. You don’t need a massive digital overhaul.

To get started, you just need to:

- choose the main folder for your notes and papers. For example, this could be a folder called “academia”

- download Zotero and Obsidian

- set up the folders within that main folder. Feel free to use my template (don’t worry if you’re not used GitHub before - you can just click ‘Code’ -> ‘Download Zip’)

- download the ‘Zotfile’, ‘Mdnotes’ and (optional) ‘Better BibTex’ plug-ins for Zotero. Configure PDF files to be saved somewhere inside your “academia” folder.

- add the Zotero Connector to your browser and save your first paper!

For the rest, you can let it gradually evolve over time. You will discover the exact pipeline and structure that works for you.

So I’d recommend setting up the basics - then test it out. Pick a few papers you’re genuinely interested in (not ones you think you should read) and get started.

I’m confident this system has 10x’d both my input and output - making the initial time investment worth it beyond a doubt.

Say Hi 👋

I have the core system in place now that I’d happily use for the rest of my life. But there’s always room for improvement and I’d love to hear your experiences. Don’t hesitate to reach out at hi@chrislovejoy.me.

If you found this helpful, consider subscribing to my personal mailing list here.

PS. One thing I haven’t touched on in this article is how to think scientifically and come up with new ideas, once you’ve learnt about the current state of affairs. This is something I’ve written about previously.

Related articles

A few other Chris’s have written detailed systems more complex and in-depth than mine:

- Comprehensive Academic Workflow from Reading to Writing in Markdown by Chris Grieser

- How I Read Research Papers with Obsidian and Zotero by Christian Bager Bach

Comments powered by Disqus.