Memorisation Techniques

Despite one’s best efforts to learn everything for understanding, there can be times where you are presented with a list of names (the branches of the external carotid artery, for example) or numbers (doses of medications) and just have to memorise them. This happens less commonly than you might think, but it does happen; and when it does, it helps to have a few memory techniques ready to enhance your mental horsepower and make keeping those details in a little easier.

This section presents just four such techniques, with links to places you can learn more, starting very simple and moving to more advanced techniques (you can find many more by googling “mneumonic techniques”). You may find all or none of these useful – it varies from person to person, and in fact this section of Chris’ great masterpiece was not written by him, because he did not use memory tricks to learn… so yeah, your mileage may vary.

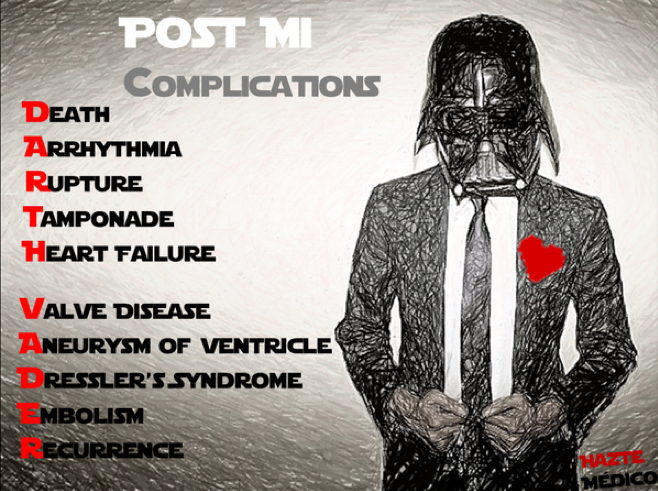

1. Letter and word mneumonics

For example: complications of myocardial infarctions as DARTH VADER, signs of cerebellar dysfunction as DANISH and the causes as PASTRIES, and the aforementioned branches of the external carotid as Some Attractive Ladies Find Older… etc etc. You can finish that one off.

Using mneumonics might seem an obvious thing, and it is – everyone uses these. However, it is worth mentioning it here for two reasons.

First, you may be unaware of just how far some people take this method of learning: for instance, http://bit.do/mnemonics-1, http://bit.do/mnemonics-2, and even http://bit.do/mnemonics-3. Second, there are better and worse ways to use these, and better and worse mneumonics. The best mneumonics are like the ones I gave above – simple, punchy, and emotionally evocative, plus every letter stands for one and only one thing. All things which make memory easier, rather than just adding another layer to remember; the only missing element is being made up by you personally, which also aids memory. Bad mneumonics are long, boring, and redundant. This is the difference between ABCDE for assessment of a sick patient, and ABCDEFGHIJ for signs of chronic hepatitis.

Signs of chronic liver disease (ABCDEFGHIJ)

- Asterixis, Ascites, Ankle oedema, Atropy of testicles

- Bruising

- Clubbing/Colour change of nails (leukonychia)

- Dupuytren’s contracture

- Encephalopathy / palmar Erythema

- Foetor hepaticus

- Gynaecomastia

- Hepatomegaly

- Increase size of parotids

- Jaundice

Increase in size of… Liver? Wait then what is the H for? Maybe it was increase in testes, I know they’re in there somewhere, and I’ve already used A three times…

2. Method of loci and story associations

So ya’know Sherlock, where the most titular detective has his very own “Mind Palace” where he can retreat to find facts and make connections in the moments between the action? Well, this is the technique he is using! Apart from, well, a realistic version rather than some feverish invention of Steven Moffat’s diseased mind. So don’t expect Benedict Cumberbatch appearing in your head to teach you about pharmacology.

The real method of loci involves using the fact that our minds seem very, very good at remembering a few things very well – particularly places (think of the town you grew up, or your primary school; how much would you bet you could still find your way around a pretty large area if dropped back there, after many years. That is a lot of information you’ve retained with very little effort!). The idea is to, as you learn, construct in your head a place, real or imaginary, and hang pieces of information in that place as memorable events, features, or else. The resulting mental structures will be highly individual (as will the success rate of this method). An example: I have the different kind of leukaemia in a court in Vauxhall where I once lived. Further away from me are the lymphoid cancers, closer the myelogenous ones (this makes sense, as lymphoid cells are a feature of the more “advanced” adaptive immune system, so you have to move further to get to them). In the far right corner (the CLL zone), are a gaggle of old men, who start cackling at you if you go too close. This is because CLL mainly affects the old (M:F 2:1), and is actually pretty asymptomatic most of the time, so they might as well laugh … and so on. Weird, right?

A related method for ordered lists is to tie the words and concepts into a story, again making it as emotionally evocative as possible. I have one for the inhibitors of CYP450 enzymes involving giant mushrooms and being thrown up on in the subway…

I’ve successfully used this kind of method to remember lists of more than 20 drugs, bacteria, or similar things after only one reading and a couple of mental revisions, and, combined with the Spaced Repetition technique described earlier, retained them indefinitely. So, it does work, but you’ll have to try it for yourself.Some resources: http://bit.do/memory-1, http://bit.do/memory-2, http://bit.do/memory-3. Basically, just google the terms.

3. Major System technique

The techniques I introduce above are great for remembering words and concepts… but a lot of the time, the hardest things to remember are numbers. What proportion of this syndrome’s sufferers are male? What is its mortality? What is the dose of co-amoxiclav? What is the half life of CRP?

The major system technique is a kind of add on which allows you to use the normal mnemonic methods on numbers as well, by simply converting them to words. It’s pretty simple in concept – you give every digit 0-9 a consonant’s sound, or range of similar sounds, as well as a meaning, and then when you need to remember a long number convert it to sounds, change the sounds to a word or phrase, and if necessary work it into a story or whatever to tie it to the concept you need it for. A simple example using my major system sounds (slightly different to the traditional sounds used by most people, for no good reason) is as follows:

Sounds:

Z

T, d

N

M

R, l

V, F

S, Sch

C, K

G, Y

P, b

Which means that the image of a meteor plunging into the ocean, releasing a spurt of bright pink flame, is…

MeTeoR DiVe PiNK, which is…

31415927, which is…

More digits of pi than I’ll ever need as a doctor, but what the hell, this was an example.

A more relevant example is: How much co-amoxiclav do you need? A ton. ToN: 1.2 grams TDS.

You get the picture. The key with this technique is to practise it a lot, and randomly – every time you see a number, in any art of life, try to convert it to its sounds as quickly as possible, or convert words to their numbers.

Resources to get you started: http://bit.do/memory-4, http://bit.do/memory-5, http://bit.do/memory-6.

4. Synesthetic memory

This might just be a typical mind fallacy thing, but I find concepts, numbers, whatever much easier to remember when they have colours, emotions, images etc associated with them. For example, in my head, all of the cytokines associated with Th2 immunity are blues and turquoises, Th1 tans, Cd8 immunity reds and warm colours. One and five are sharp numbers, four is a dark red square with rounded edges, 3 is orange, 2 feels a little uncomfortable. I do this automatically if I am learning something I’m interested in, but if I’m trying to learn something I’m less excited about have to do it manually, so to speak, and it helps.

Continued in Bonus Chapter 4.

This is a chapter from The Modern Medical Student Manual. A full list of chapters are below:

- Introduction: From That Day To This Book

- Chapter 1: Medicine from Fifty Thousand Feet: Perspective, Targets and Limits

- Chapter 2: The Fundamentals of Fast Learning - Part 1 and Part 2

- Chapter 3: Mastering Clinical Medicine - Part 1 and Part 2

- Chapter 4: Increasing our Impact (and the power of Self-Education) - Part 1 and Part 2

- Chapter 5: A Scientific Approach to Research - Part 1 and Part 2

- Chapter 6: Commanding Clearer Communication - Part 1 and Part 2

- Conclusion

Plus Bonus Chapters:

- Bonus Chapter 1: If Medicine Gets You Down

- Bonus Chapter 2: Is Medicine Right For Me?

- Bonus Chapter 3: Memorisation Techniques (by Dr James Hartley)

- Bonus Chapter 4: Learning from Others in Medicine

Comments powered by Disqus.